I just went to see a fantastic career retrospective exhibition of the South African photographer David Goldblatt at the Jewish Museum here in NYC.

Goldblatt came to maturity during the darkest days of the apartheid era, and his photographs document the oppression meted out to the non-white majority in South Africa in the most visceral way. Here, for example, is a shot of his of a young man recently out of police detention. The severity of the interrogation methods routinely employed by the South African police are glaringly apparent in the two casts which encase the young man’s arms.

Goldblatt came to maturity during the darkest days of the apartheid era, and his photographs document the oppression meted out to the non-white majority in South Africa in the most visceral way. Here, for example, is a shot of his of a young man recently out of police detention. The severity of the interrogation methods routinely employed by the South African police are glaringly apparent in the two casts which encase the young man’s arms.

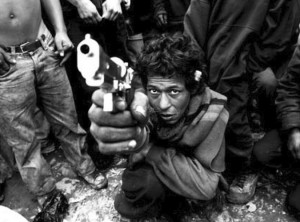

We see all of the homicidal violence of the apartheid regime in Goldblatt’s photographs. In this photo, for  example, victims of a government death squad lie splayed alongside their car. Such documentary images were crucially important to record during the apartheid era given the government’s attempt to suppress all records of its campaign of secret violence against internal critics and activists. In Deborah Hoffmann and Frances Reid’s brilliant documentary record of the Truth and Reconciliation Commision, a film called Long Night’s Journey into Day, we see the pain inflicted on a group of mothers whose sons have disappeared, leaving no trace to mourn.

example, victims of a government death squad lie splayed alongside their car. Such documentary images were crucially important to record during the apartheid era given the government’s attempt to suppress all records of its campaign of secret violence against internal critics and activists. In Deborah Hoffmann and Frances Reid’s brilliant documentary record of the Truth and Reconciliation Commision, a film called Long Night’s Journey into Day, we see the pain inflicted on a group of mothers whose sons have disappeared, leaving no trace to mourn.

Another image of Goldblatt’s from the exhibition documents the appalling policy of forced removals. In this image, a woman lies in a bed  wrapped protectively around her newborn child. We are privy to this intimate scene because the house (or shack) within which the mother and daughter had been living has been demolished, leaving them asleep under the brutal empty skies of the land.

wrapped protectively around her newborn child. We are privy to this intimate scene because the house (or shack) within which the mother and daughter had been living has been demolished, leaving them asleep under the brutal empty skies of the land.

As these photographs make clear, Goldblatt acted as a witness to the atrocities of apartheid. What they also underline is his powerful technique of focusing on the quotidian. Instead, in other words, of training his lens on protests and rallies – the stuff of standard photojournalism – Goldblatt delved into the everyday humiliations, oppressions, hypocrisies and contradictions of life under apartheid.

For me, some of Goldblatt’s most powerful work focuses on whiteness. The complexity and painfulness of this position is not always apparent. I recently sat across from a new friend in a small restaurant in Bolivia, for example, discussing what it was like to be white in South Africa. He was surprised by my talk of the ambivalences and contradictions of white consciousness during the apartheid era in South Africa. Of course, average white people in South Africa benefited massively from the apartheid regime’s oppression and exploitation of the non-white majority in the country. This needs to be stated up front and with no hesitation.

For me, some of Goldblatt’s most powerful work focuses on whiteness. The complexity and painfulness of this position is not always apparent. I recently sat across from a new friend in a small restaurant in Bolivia, for example, discussing what it was like to be white in South Africa. He was surprised by my talk of the ambivalences and contradictions of white consciousness during the apartheid era in South Africa. Of course, average white people in South Africa benefited massively from the apartheid regime’s oppression and exploitation of the non-white majority in the country. This needs to be stated up front and with no hesitation.

But while the material advantages conferred on even the poorest whites by the apartheid system are undeniable, that system nonetheless generated a traumatized sensibility among even the most privileged and cocooned of whites. In the above image, for instance, a white farm kid is caught in an eerily intimate moment with his black nanny. He stands with his arms on her shoulders. Even more powerfully, her left hand is wrapped around his foot. The intimacy in this nonchalant embrace is overwhelming, exacerbated by the fact that both of the subjects are quite beautiful and that the young black woman’s breast is showing through her flimsy jersey. The boy is on the cusp of adolescence. Soon, his childish intimacy with his nanny will shift totally. She will go from being a mother surrogate (perhaps even closer than his real mother) to become part of an alien and threatening race. The sexuality latent in Goldblatt’s photograph will become something threatening or exploitative in the extreme.

Goldblatt’s photographs of everyday life among Afrikaners are filled with this sense of latent, ominous contradiction. How, he asks his viewers and South Africans in general, could people go about everyday life in the midst of such an unspeakably evil system? This is the same question asked by Pumla Godobo-Madikizela’s A Human Being Died That Night, a memoir of this member of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission encounter with Eugene de Kock, a government assassin known popularly as “Prime Evil.” Godobo-

Goldblatt’s photographs of everyday life among Afrikaners are filled with this sense of latent, ominous contradiction. How, he asks his viewers and South Africans in general, could people go about everyday life in the midst of such an unspeakably evil system? This is the same question asked by Pumla Godobo-Madikizela’s A Human Being Died That Night, a memoir of this member of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission encounter with Eugene de Kock, a government assassin known popularly as “Prime Evil.” Godobo- Madikizela travels to a maximum security prison to interview de Kock after the collapse of apartheid. What she finds is a man rather than a monster, someone who is gradually coming to repent his crimes. The upshot is very similar to Hannah Arendt’s account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann after World War II: evil for the most part takes on a totally banal face; average people keep their heads down and focus on the minutiae of everyday life while acting in a manner that is complicit with great evil in many instances in history.

Madikizela travels to a maximum security prison to interview de Kock after the collapse of apartheid. What she finds is a man rather than a monster, someone who is gradually coming to repent his crimes. The upshot is very similar to Hannah Arendt’s account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann after World War II: evil for the most part takes on a totally banal face; average people keep their heads down and focus on the minutiae of everyday life while acting in a manner that is complicit with great evil in many instances in history.

Goldblatt’s images record just such banal evil. If they were set in the United Kingdom instead of South Africa, they might seem nothing more than dull snapshot-like records of provincial life in the 1960s and ’70s. But we as viewers know that these photographs are set in South Africa, that the golden-locked boy walking past the supermarket is likely to graduate soon and be conscripted to fight and possibly die in border wars or in suppressing township uprisings. The teenage beauty pageant contestants are living lives of artificial luxury on the backs of the majority of the South  African populace. The man mowing his lawn on a tranquil Saturday morning lives in a town forcibly purged of black residents. No doubt on some level these people knew that they were cogs in a truly evil system, but they found stories to tell themselves – stories founded in race and religion – that legitimated their relatively privileged social positions.

African populace. The man mowing his lawn on a tranquil Saturday morning lives in a town forcibly purged of black residents. No doubt on some level these people knew that they were cogs in a truly evil system, but they found stories to tell themselves – stories founded in race and religion – that legitimated their relatively privileged social positions.

Goldblatt also had a quick eye for forms of class stratification within the dominant white  class. Thus, he captures images both of the herrenvolk leaders of the National Party, the architects of apartheid, as well as of the dirt-poor Afrikaner farming families who barely

class. Thus, he captures images both of the herrenvolk leaders of the National Party, the architects of apartheid, as well as of the dirt-poor Afrikaner farming families who barely  make ends meet, despite the boon of white skin.

make ends meet, despite the boon of white skin.

Photographs of tragedies such as famine and warfare have largely ceased to shock us. Since the days of Robert Capa, muckraking photojournalism has lost much of its impact as people have grown accustomed to the society of the spectacle. Goldblatt’s photographs are different and perhaps remain effective inasmuch as they focus on intimate moments in everyday life that show the vulnerability as well as the bigotry of the South African white tribe.

Finally, the Jewish Museum show is particularly powerful as a result of the curatorial decision to present Goldblatt’s work organized along lines similar to the initial publication of much of the material. We thus see sections devoted to Goldblatt’s early work in the disappearing gold mines of Johannesburg, a project he  undertook in collaboration with Nadine Gordimer. We see his focus on individuals living in small, exclusively white towns. And we see his photographic dissection of the distorted landscapes and city-scapes of apartheid South Africa. These unpeopled urban spaces perhaps speak even more than the portraits, poignant as those are. This is a landscape blighted by the reduction of one portion of the population to the status of non-entities. Here on the right, for instance, is an image of a butcher shop that has literally been butchered, its right half removed along with the family that lived there as part of the infamous “Group Areas Act” that permitted forced removals.

undertook in collaboration with Nadine Gordimer. We see his focus on individuals living in small, exclusively white towns. And we see his photographic dissection of the distorted landscapes and city-scapes of apartheid South Africa. These unpeopled urban spaces perhaps speak even more than the portraits, poignant as those are. This is a landscape blighted by the reduction of one portion of the population to the status of non-entities. Here on the right, for instance, is an image of a butcher shop that has literally been butchered, its right half removed along with the family that lived there as part of the infamous “Group Areas Act” that permitted forced removals.

Yet, in the midst of this desolation, Goldblatt also shows us how oppressed people managed to find solace and strength in the quotidian, in rituals such as a wedding, for example. For if evil is banal and, in a place such as South Africa, ubiquitous, resistance and hope are equally evident and omnipresent in everyday life.

Yet, in the midst of this desolation, Goldblatt also shows us how oppressed people managed to find solace and strength in the quotidian, in rituals such as a wedding, for example. For if evil is banal and, in a place such as South Africa, ubiquitous, resistance and hope are equally evident and omnipresent in everyday life.