I recently attended a forum organized by New York University’s Institute for Public Knowledge. The topic was “Occupy Sandy and Emerging Forms of Social Organization.”

I recently attended a forum organized by New York University’s Institute for Public Knowledge. The topic was “Occupy Sandy and Emerging Forms of Social Organization.”

The organizers described the event in the following terms:

This Public Forum will address Occupy Sandy and Emerging Forms of Social Organization. By a number of accounts, many neighborhoods in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Sandy experienced confusion, disorganization, and a lack of engagement by city, state, or federal government agencies or traditional civil society groups. Occupy Sandy, however, in coordination with local neighborhood organizations, proved to be nimble, effective, and fast acting to help with the distribution of supplies and cleanup, and they continue to be deeply involved as neighborhoods are making decisions about rebuilding. What worked, what didn’t, and how are the ways in which people are organizing themselves shaping their ability to have an impact on communities? How can New Yorkers organize to effectively tackle the realities of decades of rising temperatures, moving flood lines, and intensifying storms?

Presenters at the event included Max Liboiron, Nick Mirzoeff, Michael Ralph, and Andrew Ross, with moderation by Harvey Moloch. For biographies of these presenters, check out the IPK site for the event.

It was a fascinating forum, one I felt was worth recording. What follows is my transcription of the talks and Q&A session that followed. Any errors in transcription are obviously my own.

Harvey Moloch: Welcome everyone. Postmodernism largely ignored nature, thinking that it would be like clay in our hands. That’s obviously not the case. We have a desperate situation. This panel responds to this situation, looking at Occupy Sandy and emerging forms of social organization.

Andrew Ross: It’s unfortunate that it takes a disaster to bring out the best in us. Disasters sometimes bring out best forms of community solidarity. Rebecca Solnit’s Paradise Built in Hell shows that distressed communities more often resort to solidarity than they do to forms of predation. Prefigurative communities that anarchists like Solnit would like to bring into being tend to arise spontaneously in disasters like the ones that Solnit studies. Rich field of disaster studies that looks at how communities create forms of resiliency and manage to rebuild after storms. Eco-disasters tends to generate common social resources that we need to fight ecological collapse, but these are resources that we don’t often manage to conjure up in face of slow-motion destruction of the planet: ocean acidification, CO2 emissions, etc.

In situations like Hurricane Sandy, people learn and earn new forms of solidarity, building on informal networks on neighborhood level. Tragedies like Sandy can set new forms of community into formation. Occupy Sandy offers Occupy movement a possibility to revive itself, and showed that spontaneous self-organization can be more effective than state organization. Experiences in trenches of Occupy Sandy inspired some activists to think more seriously about the dream of going off the grid and setting up their own autonomous urban communes.

There were other forces that were not so benign. Record of disaster capitalism that Naomi Klein has made well-known to us in The Shock Doctrine is the obverse side of story Rebecca Solnit would like to tell. Consider banks and other agencies that circled around disaster-affected communities like vultures. Miriam Greenberg and Kevin Fox-Gotham have done a study of New Orleans in wake of Hurricane Katrina that shows massive upward redistribution of wealth in wake of disaster.

It’s still too early to say how disaster capitalism will play out in relation to Sandy, although Mayor Bloomberg’s appointment of the head of Goldman Sachs to redevelopment is an early and ominous indication.

Waterfront communities all over NYC have been in transition for some time from low to high income. Fortified enclaves like Battery Park City withstood the storm quite well, and are now being seen as a model. Much of city’s public housing is situated in flood zones. What will be their fate? Ordinarily we would expect them to be cleared away for development. But land isn’t simply a commodity; it also has a social character. This is how and why the waterfront has become a site of contention. Social character of Zone A land can operate as a buffer for storm surges, but it’s also a site where people live. Voluntary retreat seems like a no-brainer, but it’s a choice that communities have to make. Here in NYC, it’s shaping up to be a classic face-off between NYC mayor and state governor. Cuomo’s plan to buy up homes in flood zones to demolish houses is being opposed by the Mayor; he’s likely to get a lavish consolation prize.

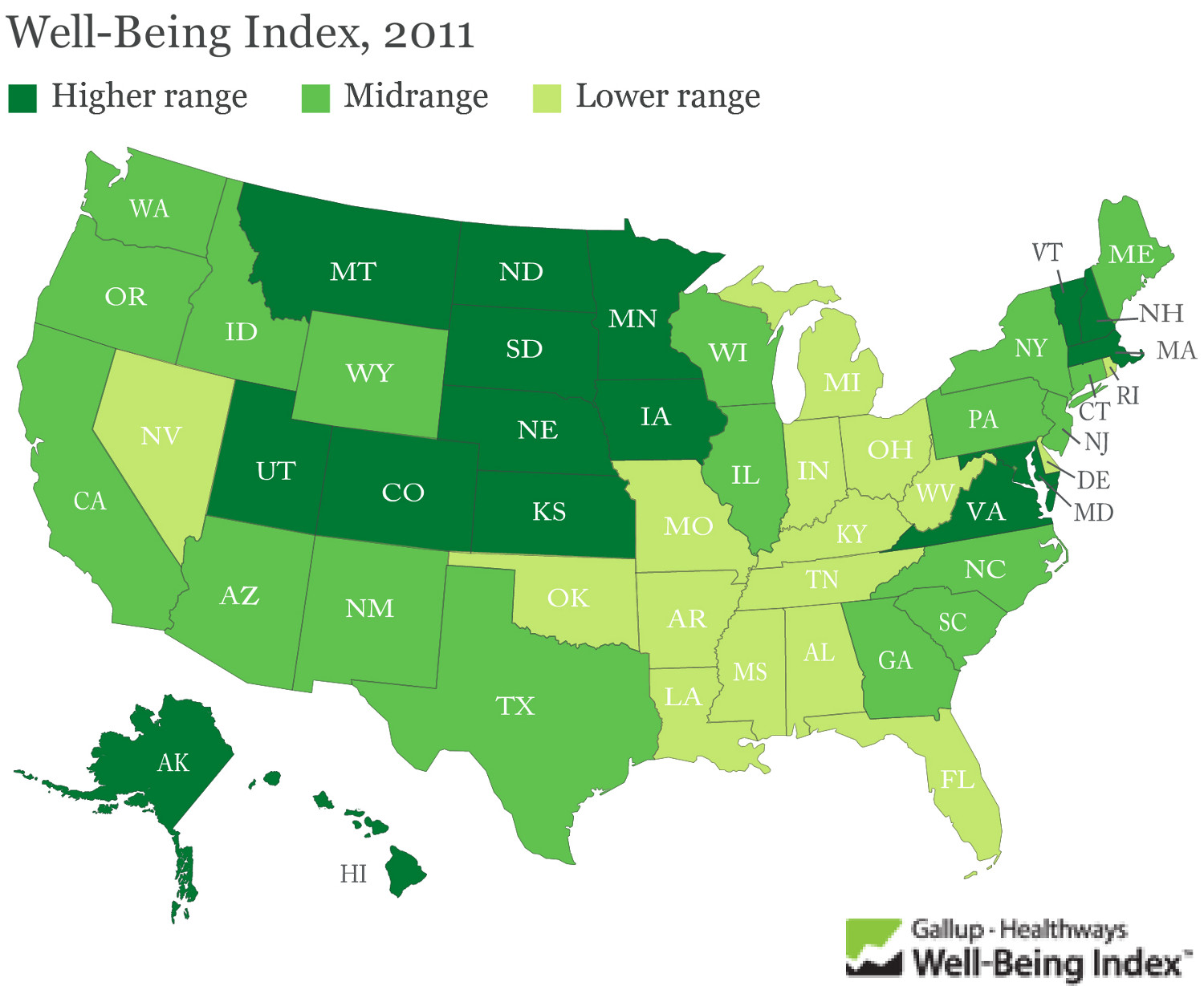

Environmental justice is aimed at combating uneven distribution of resources in metropolitan areas. Disparities in life expectancies in different parts of metro. In contrast with this approach, push to reduce carbon footprint across an entire metro area ignores disparities within the city. This is one of the ways that mayors like Bloomberg have jumped on the sustainable cities bandwagon. Platitudinous notion that climate change affects everyone. Sandy was an important watermark in the shifting mentality in urban justice. In its wake, new watchword seems to be resilience; how cities will fortify themselves in face of climate change. Window for sustsainabilty seems to be over. New mentality of adaptive resilience is about surviving the worst onslaughts. In some respects, it’s close to liveboat ethics of Garrett Hardin in 1970s. Putting resources into the defense of resource islands is a different pathway from the idea that we should be cutting emissions to allow poor cities in other parts of the world to use their carbon allotments to develop their way out of poverty. This resilience argument is a big challenge to those of us who care about climate justice and about inequality.

Michael Ralph: I recently coordinated a series of events called Alternative Spring Break NYC. One of those involved working with New York Communities for Change to survey communities in Rockaways about whether they had the means to recover from Sandy. 75% of FEMA aid comes from federal govt and 25% comes from state government. Some of this aid is available to organizations, and some to individuals. Latter tends to be very diminutive, around $3,000 per person. We saw this in wake of BP oil spill in Gulf, where aid that got to affected communities and individuals was slender. Most common financial mechanisms in wake of Sandy are federal aid in form of loans or grants.

I’d like to play you a video clip of Kenneth Feinberg, who has been appointed to oversee distribution of funds after Sandy (as well as BP oil spill and 9/11). His discussion of potential insurance claims is based on idea that insurance companies can foresee natural disasters and factor it into their calculations.

Congress only approved Sandy Relief Bill recently. Feinberg claims that insurance companies factor all these forms in. The reporter mentions that Feinberg’s discussion of insurance sounds like a derivative. Feinberg’s commentary contradicts his own record of distributing relief.

Delivery of payments can only take place if legal causality can be proved. FEMA classifies Sandy as a hurricane, while  Storm Center classifies it as a tropical storm, meaning that insurers won’t have to pay out. Insurers have policies that include anti-concurrent policies, which mean that homes destroyed by multiple forces of nature are not going to be covered.

Storm Center classifies it as a tropical storm, meaning that insurers won’t have to pay out. Insurers have policies that include anti-concurrent policies, which mean that homes destroyed by multiple forces of nature are not going to be covered.

Many New Yorkers don’t have flood insurance, which is available through FEMA, but provided by private companies. The problem here is that FEMA guarantees a certain amount of coverage to firms to draw them into a national insurance program, but they then benefit from this program even if they don’t provide adequate relief to disaster victims.

Insurance becomes a site where people can contest established regimes of finance capital, which tends to be the primary means for adjudicating environmental crises.

Max Liboiron: I and my comrades at the SuperStorm Research Lab have been interviewing different stakeholder groups about their experience of Sandy, including policy makers, businesses, volunteers and first responders, and residents effected by the storm. We’re interviewing people every 6 months to see how stories develop over time.

I’m going to outline how grassroots responders tend to organize space and time differently from state agencies, which leads to different definitions of crisis and aid. It’s not a case of government “screwing up,” but that there’s something foundational to the structure of government that prevents it acting like autonomous groups such as Occupy Sandy.

Government is always too slow, according to descriptions, while Occupy Sandy is seen as nimble.

Ubiquitously people talked about government being absent during and after Sandy. What we’re dealing with here is government that matters as opposed to pure spatial proximity. Neighborhoods went off the grid, ending up working like and with community organizations like Occupy Sandy.

This results in very different types of aid, a social justice problem. People say that FEMA came in but didn’t help people living in public housing. So the aid that did get in tended to be people from the community.

Another issue is that houses of worship are not eligible for FEMA aid, but such sites were critical.

In addition, deadlines are a big problem for many people. Filling in forms requires a huge amount of time.

Finally, nationalization of spatial boundaries meant that many people affected by storm who are not US citizens are not eligible for aid. So organizations like Occupy Sandy had to figure out how to dispense aid without asking about citizenship status.

Occupy Sandy coming out of Occupy Wall Street movement, so there’s a refusal to require people to identify themselves in order to help. This also goes for who can help: anyone can help. Occupy Sandy folks talk about the importance of the flexibility of roles, which makes the organization far more nimble and able to escape silos.

Temporality of disasters. Government agencies spend a lot of time drawing deadlines and deciding when aid will no longer be available. But Occupy Sandy is clear about the fact that Sandy is a moment in a broader crisis. Things go back to the low-level crisis point where they were. That’s why Occupy Sandy moves to mutual aid. This is also why organizers are moving out of Sandy-affected areas to deal with crisis in other areas.

There’s lots of discussion of “We Got This” – idea that mutual aid is solution to governance crisis. But then critics say that state has to have responsibility for redistributing resources and keeping certain infrastructure going.

Problem that different government agencies don’t talk to one another; this is problem of silo. When storm hits, Mayor Bloomberg calls Police Chief Kelly rather than his Office of Emergency Management.

Nick Mirzoeff: What is the emerging possibility that comes out of experience of Sandy and Occupy Sandy? One of the emerging social possibilities, I want to argue, is revolution.

One way of thinking about this: rise of CO2, which has put us at over 400ppm. Last time this happened was 3.5 million years ago, when there were mastodons. 350ppm is level at which we’re supposed to be safe. 400ppm is revolution; we’re no longer in frame of evolution but revolution since humans have altered all the contexts in which social life unfolds. We have no clear sense of where things will go from here.

On the other side, we should be talking about what Occupy Sandy did. If you were looking for a record of what OS did from the established media, you’d have trouble figuring out what happened. There was, for example, an article in NYTimes on May 1 which quoted Occupy spokesman said that OS is not revolutionary. What did he mean? He meant that Occupy isn’t like a traditional revolutionary movements since it’s based on mutual aid. Social movements are based not on social Darwinist competition, but rather on solidarity. The idea that social life is conducive to mutual aid is revolutionary.

We’re going to have to establish prosperity without growth. Instead of growing our way out of crisis, we’re going to have to figure out a way of redistributing what we have.

But we also have to think about the fact that the event of Sandy was a leap. Rockaway boardwalk was totally destroyed. People just rolled up their sleeves and pitched in. Patterns of organizing that had been established at Zucotti Park were quickly reproduced, but this time it wasn’t about sustaining people in park but people who needed help throughout the city. Occupy doesn’t have any preconditions: if you need, you get. This is democratic in the oldest possible definition.

Also, we have a pivot, a moment at which people change their points of view. There’s been no questioning that Sandy was caused by climate change. This wasn’t true for Irene. What this represents is a palpable change in attitudes towards climate change. People are now really interested in ideas like climate debt.

Just because we haven’t had a climate agreement since November doesn’t mean that people don’t care about climate change. EU’s attempt to create carbon market has collapsed. EU’s climate footprint doesn’t factor in production of good in China.

We need to reconfigure climate justice. We’ve tended to use it in terms of charity: we’ll give up our carbon emissions because we’re good people. This was never likely to happen. It gets much more interesting when we begin to think about revolutionary politics.

Tar Sands is one of the next major struggles we face. That oil will be burned in China. Massive pollution in Chinese cities, where we’re sending our students. Chinese people are beginning to rise up against such pollution. At this point, it becomes possible to create international connections and think about climate justice not as charity but as mutual aid.

This may sound abstract, but we need to keep in mind that we’ve been living for the last 20 years with huge experiment to create communication exchange: internet. We can share knowledge in a way that we never could previously. We can’t let elites depress us about the current situation. We should see it as an opportunity to create solidarity.

Questions and Answers:

Q: Do different stakeholders you talked to, Max, agree about ecological causes?

Max: No, people don’t necessarily agree that Sandy was created by climate change, but they all agree that climate is changing. So climate change has become a brand that people don’t identify with. Also, another person we interviewed identified banks as a problem.

Q: Can you talk about Occupy Sandy’s social media use and implications for disaster management?

Max: I’m part of Occupy Data, and I can tell you that no one can agree about how social media are used. Social networks are not all online. Tweets were not coming out of disaster-affected areas because people didn’t have electricity. We need to have better communication strategy – some people argue that it needs to be paper. There’s lots of disagreement on this regard.

Nick: Amazon was used by Occupy Sandy to specify exactly what kinds of things were needed, in a kind of online “wedding list”. This allowed organizers to get the things they needed.

Michael: When we were doing interviews in Rockaways, we had to go door to door. Many people would only respond if they could connect with you on a personal level.

Andrew: When we’re talking about climate justice, the core principle is climate debt, which needs to be paid by Northern nations to Southern nations. Part of the problem has been the nation-state framework, which has been the approach when trying to adjudicate climate change agremeents. Perhaps cities, whch have been far more progressive in this regard, could be key site for recognizing climate debts and thinking of innovative ways of paying off these debts. In addition, once you break down nation-state framework, you can begin to see uneven effects of climate change, both within a nation and within metropolitan regions. When you begin to look at plans like that of Bloomberg, you find out that they’re mostly plans for economic development or cost avoidance. There are no sustainability plans which are vehicles for civil rights, for paying back debts to sidelining of populations historically. Global movement for climate justice is modeled on US movement of environmental justice in 1980s and 1990s; Bali Declaration is explicitly modeled on EJ movement that preceded. Rhetoric of mutual aid has to be thought about carefully because notion of aid depoliticizes debt owed as a result of uneven development. We need to introduce a language of indebtedness and obligation, which takes us to a different level of social bonding and interactivity than language of aid.

Q: I’m one of the founders of Rockaway Emergency Plan. Social Media was crucial on day of storm, and after. We used social media to get hundreds of people to turn out. Even today we’re using FB and Twitter to engage community. But my question is for Andrew, about disaster capitalism. There’s a lot of distrust and nervousness about how things are being rebuilt. How can we protect communities against disaster capitalism; it seems like a lot of things are out of people’s control. For example, we’re seeing how rebuilding of the boardwalk is out of control.

Andrew: you need to have watchdogs who stay on the job 24/7, disseminating information about the actors. It’s often difficult since predators make deals individually. State makes collective deals so it’s often see when it’s assisting capital. But it’s harder when predators operate in dark, as with bad loans for disaster-affected communities. We can see what’s happening at the level of the state: Cuomo vs Bloomberg plans. Under latter, land that is liberated by demolitions can be sold to developers. That’s a huge difference.

Michael: part of what complicates the plans of developers is bad PR, as well as work by lawyers who are willing to do pro bono work.

Andrew: We have a real opportunity in the upcoming mayoral elections to highlight many of these issues.

Q: Hard vs soft social organizations. How do things stay nimble and yet be sustained?

Max: we asked this in our interviews, and best answer was undesignated common space. For example, houses of worship functioned as key nodes where people could congregate and organize in disaster situations.

Michael: I take Andrew’s point about problem of language of aid, but I think mutual aid is nonetheless an important concept. Insurance companies purport to replace institutions of community mutual aid, but they often don’t do this at all. So by emphasizing mutual aid, we challenge ethos of financialization that undergirds much of the insurance industry.

Nick: In the wake of slavery, people asked for a Jubilee – 40 acres and a mule, which would have made their lives sustainable. Today, people are trying to maintain their systems of mutual aid in places like Rockaways. We need to build these kinds of links between cities. If we want to claim a commons in this city, the NYPD beat the hell out of us and closed hubs.

Andrew: Watch what you wish for: there’s a very thin line between left and right wing libertarianism. Colin Ward, the British anarchist planner, had a formative experiencew when working with govt relief agencies in Lima earthquake. His analysis was that self-organization was much more effective than relief organizations. This is taken up as model by UN: sites and services model, which is thinnest form of relief you can image. It takes on neoliberal template. This approach can happen very quickly. So, although I’m an advocate of the commons, I’m not about to give up on public provision, because there are things that don’t scale up, particularly when we’re talking about infrastructure. It’s absolutely necessary to transition infrastructure away from its current status quo. We don’t have time to scale up molecular organization to level of the state. We need a good state, and we need it now.

The campaign to divest from fossil fuels continues to pick up steam on campuses around the US and throughout the rest of the world. Only days ago the Norwegian parliament voted to divest its country’s sovereign wealth fund from investments in coal. This is a huge victory: Norway was one of the world’s top ten investors in the global coal industry.

The campaign to divest from fossil fuels continues to pick up steam on campuses around the US and throughout the rest of the world. Only days ago the Norwegian parliament voted to divest its country’s sovereign wealth fund from investments in coal. This is a huge victory: Norway was one of the world’s top ten investors in the global coal industry.