Coal is the big dirty secret of our time. When we turn on our sleekly designed iPads and MacBooks, we seldom consider that the energy used to power these totems of the global economy is derived from fiery combustion of the fossilized remains of massive Paleozoic plants. Nor do we often think about the human labor or environmental toll associated with the consumption of power today.

Coal is the big dirty secret of our time. When we turn on our sleekly designed iPads and MacBooks, we seldom consider that the energy used to power these totems of the global economy is derived from fiery combustion of the fossilized remains of massive Paleozoic plants. Nor do we often think about the human labor or environmental toll associated with the consumption of power today.

How else can one explain advertising campaigns such as that associated with the Nissan Leaf, an electric car which, as its name suggests, is represented as an embodiment of pristine nature despite the fact that its power source is more environmentally destructive than gasoline?

Although coal-fired power plants provide more than 50% of the electricity currently consumed in the US, when they stop to reflect on where their power comes from few Americans think about coal. The tense diplomatic brinksmanship associated with global oil supplies occupies a far more prominent place in news headlines than discussions of coal, yet 35% of the world’s electricity is currently generated by coal power, and developing nations such as China and India bring hundreds of pollution-belching coal-fired power plants online each year.

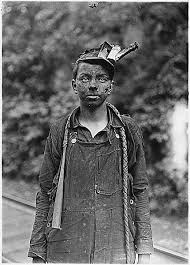

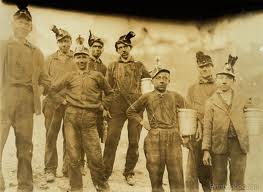

To consider coal is to step into a time machine that transports us not just back to the origins of terrestrial life, but to the  more proximate human inventions and struggles that gave birth to modernity. The sulfurous odor given off by burning coal meant that it was long associated with dark satanic powers. Despite fueling industrial revolutions in countries such as Britain, Germany, and the United States, coal was always regarded with ambivalence and even fear, its life altering energy ineluctably linked to forces of physical and racial degeneration. For much of the last half-century, the Age of Oil, coal has been associated with a bygone time, the era of King Coal. But coal is no longer invisible. As a major contributor to anthropogenic climate change, coal once again appears to hold the key to our collective future.

more proximate human inventions and struggles that gave birth to modernity. The sulfurous odor given off by burning coal meant that it was long associated with dark satanic powers. Despite fueling industrial revolutions in countries such as Britain, Germany, and the United States, coal was always regarded with ambivalence and even fear, its life altering energy ineluctably linked to forces of physical and racial degeneration. For much of the last half-century, the Age of Oil, coal has been associated with a bygone time, the era of King Coal. But coal is no longer invisible. As a major contributor to anthropogenic climate change, coal once again appears to hold the key to our collective future.

To stop today’s coal boom, the climate justice movement must make coal’s environmental and political toxicity visible. The campaign against coal can draw strength from the historical memory not simply of the importance of miners in the struggle to deepen democracy in industrialized nations, but also from the specific weaknesses of the coal industry’s infrastructure. Climate and environmental justice movements need to join with workers in the energy sector to choke the infrastructure of coal.

However, as the British film Brassed Off reminds us, workers will fight to retain their jobs in a dirty industry that kills them unless they are offered a clear alternative. The campaign against coal must therefore demand a just transition to a renewable, decentralized energy infrastructure.

We have powerful imaginative resources to mobilize in this regard. After all, the figure of King Coal reminds us that the energy infrastructure created by what Lewis Mumford called carboniferous capitalism has bred rampantly undemocratic forms of corporate oligopoly. Taking power thus implies a radical democratic transformation of both global energy systems and governance. Let us dethrone Old King Coal.