A squad of twelve Marines edges into the home of an Afghani villager named Omar, whom they have learned is sympathetic to U.S. forces and wants to exchange information about enemy insurgents for help with his broken generator. While the squad is in Omar’s home, however, a woman whom they find out is his mother grows increasingly agitated. Her husband has been killed by Coalition air strikes, and, upset about the presence of so many soldiers in her home, she begins to yell at Omar to get them out of the house. How will the squad leader react to the curses of Omar’s mother, uttered in a language he doesn’t understand? While Omar is initially calm and courteous, his behavior changes markedly if the squad overreacts to his mother’s yelling. Will the squad succeed in extracting information from Omar and in maintaining calm?

A squad of twelve Marines edges into the home of an Afghani villager named Omar, whom they have learned is sympathetic to U.S. forces and wants to exchange information about enemy insurgents for help with his broken generator. While the squad is in Omar’s home, however, a woman whom they find out is his mother grows increasingly agitated. Her husband has been killed by Coalition air strikes, and, upset about the presence of so many soldiers in her home, she begins to yell at Omar to get them out of the house. How will the squad leader react to the curses of Omar’s mother, uttered in a language he doesn’t understand? While Omar is initially calm and courteous, his behavior changes markedly if the squad overreacts to his mother’s yelling. Will the squad succeed in extracting information from Omar and in maintaining calm?

Along with the explosion of an improvised explosive device at an Afghani police recruitment center and a coordinated attack on an isolated base, this scenario unfolds in a virtual Afghanistan located inside the Combat Hunter Action and Observation Simulation (CHAOS) exercise in Camp Pendleton’s Infantry Immersion Trainer (IIT) virtual environment. Part of U.S. Joint Forces Command’s Future Immersive Training Environment (FITE) scheme, the CHAOS exercise was developed with the help of the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT), creating a simulated experience through which soon-to-be-deployed Marines interact with live role players while realistic virtual sights, smells, and sounds, as well as animatronic figures, mimic the Afghani reality they will soon encounter. Jay Reist, FITE operations manager, opined that the aptly named CHAOS exercise is “not about the gadgets… We’ve focused on figuring out how people make complex decisions in sensory-overloaded environments and what we need to do to achieve that realism in training.”[i]

FITE and CHAOS are part of a series of simulation exercises developed by the U.S. military in recent years to help troops deal with a relatively new reality, the anarchic experience of what the armed forces term Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT). The virtual and mixed-reality exercises carried out in the FITE program are not so distant from the forms of virtual gaming available online through military-sponsored programs such as America’s Army and Full Spectrum Warrior. These sophisticated games are also available to civilians, offering a potent recruitment tool as well as a visceral experience of the forms of hypercapitalized militarism that characterize U.S imperialism today. In this presentation, I explore the genealogy of these games’ representation of the urban space of empire. Looking in particular at Calcutta under the British Raj and Algiers under the French, I argue that the visual economy of urban empire is constituted by increasingly sophisticated scopophilic representational technologies that paradoxically produce an ever-more disembodied imperial cybernetic subject. If, that is, imperial visual technologies have become far more capable of peeling back the skin of the city to reveal the urban viscera that lie beneath, the colonial gaze remains enduringly phobic about the forms of corporeal propinquity that result. The upshot today is a turn towards forms of virtuality such as robotic warfare that help to legitimate notions of virtuous imperial war.

As the high visibility of urban environments in Joint Operation Environment (JOE) 2010, U.S. Joint Forces Command’s most recent strategic document, suggests, the military is highly aware of the urbanization of warfare over the last three decades. If the paradigmatic image of the Vietnam War was the burning village, today’s key icon of war is the rioutous city. It wasn’t supposed to be this way. In the late 1980s, Pentagon theorists began discussing a so-called Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) that would endow the US with unparalleled “full spectrum dominance.”[ii] In many ways this was a reaction to the protest catalyzed by Vietnam; in fact, US commander General William Westmoreland famously predicted the future automation of warfare in reaction to the guerrilla tactics of anti-colonial insurgents in the late 1960s.[iii] By the 1980s, military theorists were doing their best to realize Westmoreland’s vision, arguing that the US could use cutting edge networked information technology to vault beyond all potential military antagonists in the same manner that the Germans’ use of coordinated air- and armored-assaults had handed them primacy in the blitzkrieg against continental Europe at the onset of World War II. As James Del Derian has remarked, the ferocious destructive potential of US military technology as it developed in the 1990s had the paradoxical effect of strengthening the belief in virtuous warfare by allowing civilian and military leaders to unleash violence from a distance and by remote control – with few to no American casualties.[iv] The satellite-controlled destruction that rained down on Iraqi forces retreating from Kuwait during the first Gulf War seemed to confirm the hype associated with the Revolution in Military Affairs, helping to exorcise the ghost of Vietnam by banishing fears about US casualties in a protracted ground war.

Yet these visions of god-like military supremacy quickly dissolved as war went urban. For much of the military, the urbanization of war was a product of the US’s overwhelming hegemony in traditional combat. In order to explain Operation Urban Resolve, a Joint Forces Command war gaming “experiment” that I attended several years ago, for example, spokesmen cited the US superiority as a primary factor for insurgents’ move to urban terrain:

The explosive growth of the world’s major urban centers, changes in enemy strategies, and the global war on terror have made the urban battlespace potentially decisive and virtually unavoidable. Some of our most advanced military systems do not work as well in urban areas as they do in open terrain. Therefore, joint and coalition forces should expect that future opponents will choose to operate in urban environments to try to level the huge disparity between our military and technological capabilities and theirs.

Given the military’s renewed interest in urban constabulary actions, it is worth looking back at colonial representations of urban space to see how the imperial gaze constructs city culture. Keeping in mind Henri Lefebvre’s seminal arguments about the way in which the city does not simply express social relations but rather shapes and produces them, we will want to pay particular attention to the ways in which the imperial gaze navigates the social relations played out in the colonial city, seeking not simply to lay bare these social relations to its inquisitive eye but also to transform those relations through processes of representing, surveying, and cataloguing. To what extent, we will want to consider, does such colonial urban scopophilia anticipate the technologies of representation deployed in the new urban wars?

For heuristic purposes I initiate this discussion of the visual economy of empire in Calcutta under the British Raj, but, as I hope to demonstrate, similar dynamics were at play in many if not all colonial cities. British artists in Bengal in the late 18th and early 19th centuries were confronted by a terrain that lacked the ideally variegated topography inherited from the Italian landscape tradition; Bengal was, after all, mainly flat swampland. In place of sublime mountains and lakes, however, British artists such as William Hodges and William Daniell added lustre to their depictions of Bengal by focusing on the picturesque decaying remains of the Mughal Empire in the region . These crumbling, vine-strewn mosques piqued the European fascination with lost civilizations and sparked a craze for Oriental architecture in late 18th century Britain. At the same time, though, such images legitimated the expansionist designs of the East India Company in Bengal by suggesting that Indian civilization was in a phase of decadence, unable to develop the land adequately and incapable of ruling itself.

. These crumbling, vine-strewn mosques piqued the European fascination with lost civilizations and sparked a craze for Oriental architecture in late 18th century Britain. At the same time, though, such images legitimated the expansionist designs of the East India Company in Bengal by suggesting that Indian civilization was in a phase of decadence, unable to develop the land adequately and incapable of ruling itself.

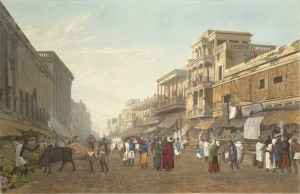

When they turned to representations of Bengali cities such as Calcutta, British artists redeployed such pictorial codes, creating a panorama that mixed vibrant commerce with what looked to an aristocratic European eye to be brutish squalor and decay. In James Baillie Fraser’s “A View of the Bazaar Leading to Chitpore Road” of 1819, for example, we see precisely this combination of desire and dread in the European colonial gaze. Fraser’s painting catalogues the tremendous variety of wares for sale in the Calcutta  bazaar, but also depicts decaying buildings and native bodies in various states. This ambivalent visual economy was paralleled by accounts of urban space in contemporary travel narratives.

bazaar, but also depicts decaying buildings and native bodies in various states. This ambivalent visual economy was paralleled by accounts of urban space in contemporary travel narratives.

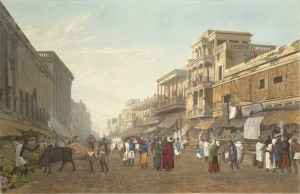

Representations of the European portions of Calcutta could not been more starkly different. Here, artists such as Thomas Daniells depicted a neo-classical idyll in which the orderly symmetry of the administrative buildings of the East India Company lends visual and moral authority to British rule in Bengal . In this  image, taken from James Baillie Fraser’s “Views of Calcutta and Its Environs” (1826), we see Government House, the seat of East India Company rule. In the distance, just in front of the massive neoclassical company headquarters, we catch a glimpse of Governor General Lord Hastings about to set off for a drive, with his carriage and bodyguard awaiting. The segregationist intentions of colonial urbanism are made quite evident by the separation of the well-trafficked roadway in the foreground of Fraser’s painting from the grounds of Government House, which is set off by an iron railing on a plinth that is interrupted by four triumphal gateways at both ends of the carriageways running across the north and south facades of the building.

image, taken from James Baillie Fraser’s “Views of Calcutta and Its Environs” (1826), we see Government House, the seat of East India Company rule. In the distance, just in front of the massive neoclassical company headquarters, we catch a glimpse of Governor General Lord Hastings about to set off for a drive, with his carriage and bodyguard awaiting. The segregationist intentions of colonial urbanism are made quite evident by the separation of the well-trafficked roadway in the foreground of Fraser’s painting from the grounds of Government House, which is set off by an iron railing on a plinth that is interrupted by four triumphal gateways at both ends of the carriageways running across the north and south facades of the building.

As these images of Calcutta under the Raj suggest, the visual economy of urban empire was underpinned by a broader representational politics that suggested that Europeans alone had the right to occupy the key institutional sites of city space. In her discussion of representations of Calcutta, Swati Chattopadhyay argues that Orientalist discourses represented authentic India as grounded in village life, cultural antiquity, and defective theocracy.[v] Similarly, in discussing colonial rule in Africa, Mahmood Mamdani makes an analogous point, arguing that the colonial state in Africa was “bifurcated, with different modes of power in rural and urban areas. Urban power spoke the language of civil society and civil rights, rural power of community and culture. Civil power claimed to protect rights, customary power pledged to enforce tradition.”[vi] If, in other words, colonial rural areas were the space of authentic colonial subjects, the city was the space of the European citizen, transplanted from Britain or France, as the case may be, in order to administer the extraction of natural wealth and labor that was the underlying rationale of empire.

This neat Manichean division of colonial space was a convenient fiction of empire, one that had little to do with the quotidian realities of colonial power. As James Baillie Fraser’s representations of early nineteenth century Calcutta suggest, everyday life in Indian cities for European colonials involved inevitable propinquity to Indian officials, merchants, concubines, and servants of many different kinds. Moreover, as Chattopadhyay convincingly shows, the myth of “dual cities” divided into segregated “white” and “black” towns is based on imperial narratives of difference and superiority that were belied in Calcutta by the constant blurring of spatial boundaries as heterogeneous populations moved in and out of particular portions of the city and as specific buildings were put to heterogeneous uses.[vii]

This neat Manichean division of colonial space was a convenient fiction of empire, one that had little to do with the quotidian realities of colonial power. As James Baillie Fraser’s representations of early nineteenth century Calcutta suggest, everyday life in Indian cities for European colonials involved inevitable propinquity to Indian officials, merchants, concubines, and servants of many different kinds. Moreover, as Chattopadhyay convincingly shows, the myth of “dual cities” divided into segregated “white” and “black” towns is based on imperial narratives of difference and superiority that were belied in Calcutta by the constant blurring of spatial boundaries as heterogeneous populations moved in and out of particular portions of the city and as specific buildings were put to heterogeneous uses.[vii]

These regulatory fictions of spatialized racial difference were nonetheless extremely powerful, and continued to overwrite empirical realities that demonstrated precisely the opposite. By 1847, for example, James Snow had discovered the water-borne nature of the cholera epidemic that decimated Britain after traveling across the Eurasian continent from Bengal in the early 19th century. Yet colonial medicine in India retained its belief in a miasmic theory of disease that emphasized the danger of noxious airborne contaminants, which were in turn connected in texts such as James Ranald Martin’s seminal Notes on the Medical Topography of Calcutta of 1836 to the notion that disease was produced by a combination of the insalubrious tropical climate and the lax morals of the indigenous inhabitants of the city. By the mid-19th century, colonial medical discourse had shifted from the notion of “seasoning” Europeans to the tropical climate that had prevailed in earlier centuries to sanitary paradigms based on mapping disease onto a biopolitical grid of race, religion, and caste difference in order to establish a cordon sanitaire around the aptly named European civil lines and military cantonments. Cholera maps such as this one, produced in 1886, represented the native precincts of the city as a  pathological space, its unsanitary conditions linked to superstitious, pre-modern beliefs. The epidemiological mapping of colonial urban space was linked to broader biopolitical and cultural practices of urban segregation. As Anthony King put it in his still-valuable study of colonial urbanism, “above all else, the [European] compound was a culture area, an area modified to express the value-system of the metropolitan society as interpreted by colonal community. In conditions of exile, creation of this environment was instrumental in maintaining a sense of identity.”[viii] The aim was to create a rigidly differentiated, systematically hierarchized, and therefore thorougly salubrious space of imperial urban spectacle, a goal that necessitated the transfer of the Raj’s capital to Delhi and, ultimately, the construction of New Delhi.

pathological space, its unsanitary conditions linked to superstitious, pre-modern beliefs. The epidemiological mapping of colonial urban space was linked to broader biopolitical and cultural practices of urban segregation. As Anthony King put it in his still-valuable study of colonial urbanism, “above all else, the [European] compound was a culture area, an area modified to express the value-system of the metropolitan society as interpreted by colonal community. In conditions of exile, creation of this environment was instrumental in maintaining a sense of identity.”[viii] The aim was to create a rigidly differentiated, systematically hierarchized, and therefore thorougly salubrious space of imperial urban spectacle, a goal that necessitated the transfer of the Raj’s capital to Delhi and, ultimately, the construction of New Delhi.

The invention of a verticle axis of vision through which urban space could be catalogued – evident in the cholera map I just displayed – was an important component in legitimating and facilitating this politics of the imperial cordon sanitaire. By lifting the viewer above the incessantly mutable hurly burly of everyday life in the colonial city, representations such as the cholera map constituted a powerful representational technology that could quantify and freeze urban space into a decipherable and actionable set of discrete segments. Yet this verticle axis of the urban visual economy always existed in tension with the horizontal axis, through which the often opaque but always titillating flow of city life could be recorded. Nonetheless, technological changes of the late 19th and early 20th century added to the potency of the vertical axis, as first photography and then cinema allowed the imperial gaze to adopt a bird’s-eye perspective. As we shall see, the bird’s-eye ultimately became a bombardier’s point of view. These transformations in the visual economy of urban empire are particularly evident in the Maghreb, where the invention of aerial bombardment in fact took place in 1911. I turn now to a discussion of representations of Algiers under French rule that illustrates these mutations in the visual economy of urban empire particularly powerfully.

Just as in India under the British Raj, the primary dynamic driving the production of urban space following the French colonization of Algeria in the mid-19th century was the engineering of racial segregation. One of the first comprehensive designs for Algiers, Charles-Fréderick Chassériau’s plan of the 1860s, carried out the effective division of the city into a European zone, the Marine Quarter, which was firmly separated from the indigenous casbah on the densely populated hills above by a broad boulevard.[ix] This principle of segregation remained of cardinal importance into the modern period, as the influential experimental plans of Le Corbusier for the city’s development in the 1930s demonstrate.

Just as in India under the British Raj, the primary dynamic driving the production of urban space following the French colonization of Algeria in the mid-19th century was the engineering of racial segregation. One of the first comprehensive designs for Algiers, Charles-Fréderick Chassériau’s plan of the 1860s, carried out the effective division of the city into a European zone, the Marine Quarter, which was firmly separated from the indigenous casbah on the densely populated hills above by a broad boulevard.[ix] This principle of segregation remained of cardinal importance into the modern period, as the influential experimental plans of Le Corbusier for the city’s development in the 1930s demonstrate.  As in other colonial cities, French urban planners in Algiers evinced a lively concern with the creation of clean, well-ventilated spaces.[x] Located outside the cordon sanitaire that putatively insulated European colonial society, the casbah during the colonial era exemplified the original dynamic that Foucault identified within biopower: a race war in which the tag “society must be defended” comes to legitimate the deployment of forms of power that blur the boundary between regulation and warfare. Indeed, the colonial city demonstrates the fallacy of assuming that regulation and warfare are antinomies; only by ignoring the Manichean spaces of the colony can these two apparatuses of power be seen as opposed to one another.[xi]

As in other colonial cities, French urban planners in Algiers evinced a lively concern with the creation of clean, well-ventilated spaces.[x] Located outside the cordon sanitaire that putatively insulated European colonial society, the casbah during the colonial era exemplified the original dynamic that Foucault identified within biopower: a race war in which the tag “society must be defended” comes to legitimate the deployment of forms of power that blur the boundary between regulation and warfare. Indeed, the colonial city demonstrates the fallacy of assuming that regulation and warfare are antinomies; only by ignoring the Manichean spaces of the colony can these two apparatuses of power be seen as opposed to one another.[xi]

Despite its association with racial alterity and contamination, the casbah nevertheless always exerted a strong pull on the French colonial imaginary. European writers and painters alike found the casbah’s sweeping wall of whitewashed houses with their rooftop terraces irresistibly picturesque. The fascination of the casbah for the Orientalist gaze lay not simply in its dramatic vertical architectonic qualities, however, but also in the specific interplay of public and private space that characterized the area. While she is critical of sweeping stereotypes concerning “the Muslim city,” urban historian Janet Abu-Lughod nonetheless argues that Islam did shape social, political, and legal institutions in the cities of the Maghreb, and that gender segregation was perhaps the foremost concern molding the urban fabric in the region.[xii] As a result of this emphasis, public spaces such as streets in Algiers tended to be the domain of men, while women occupied the domestic spaces of traditional houses. Because of these gendered codes and the climatic qualities of the region, areas such as the Algiers casbah were composed of narrow, twisting alleys bordered by high, nearly uninterrupted building facades. Inside these blank walls, however, traditional houses opened out onto courtyards surrounded by arcades. In addition, the serried rooftop terraces of the casbah provided a common living space that allowed women in different buildings to communicate with one another. The frisson of difference and mystery generated by this architecture of gendered seclusion proved endlessly provocative for French urbanists and colonial policymakers.

In fact, the lure of the casbah, represented in metonymic form as a feminized other, was rampant in French colonial culture. The prototypical image in this regard is, of course, Delacroix’s 1834 painting “Femmes d’Alger Dans Leur  Appartement”. Delacroix’s painting gains its power not simply by laying bare the exotic garb and proscribed flesh of a group of Algerian women, but also through the fantasy it unfolds of effortless penetration into the hidden sanctum of the Algerian house.[xiii] These themes of voyeuristic penetration into proscribed spaces, and the objectification of women that went along with such male fantasies, are repeatedly obsessively throughout the late nineteenth and into the twentieth century. The seductive character of these representations of oriental mystery and sexuality in academic art became even more prurient after the invention of photography catalyzed a lively trade in pornographic postcards of Northern African women.[xiv]

Appartement”. Delacroix’s painting gains its power not simply by laying bare the exotic garb and proscribed flesh of a group of Algerian women, but also through the fantasy it unfolds of effortless penetration into the hidden sanctum of the Algerian house.[xiii] These themes of voyeuristic penetration into proscribed spaces, and the objectification of women that went along with such male fantasies, are repeatedly obsessively throughout the late nineteenth and into the twentieth century. The seductive character of these representations of oriental mystery and sexuality in academic art became even more prurient after the invention of photography catalyzed a lively trade in pornographic postcards of Northern African women.[xiv]

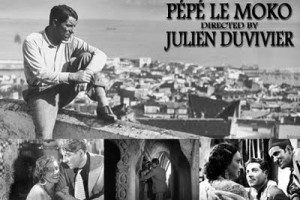

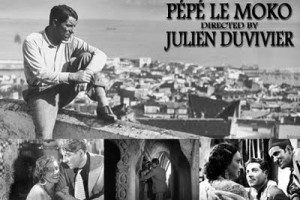

Such imperial urban scopophilia reached a crescendo as cinema turned to the colonies for subject matter. Julien  Duvivier’s Pépé le moko of 1937 offers us the tale of a French gangster who goes to ground in the casbah, represented in the film as an impenetrable space of multiracial, polyglot, feminized alterity. In Duvivier’s film, the dashing gangster Pépé is ultimately undone by his desire for a Parisian woman who penetrates into his lair in the casbah, suggesting that he has become unmanned despite his tough-guy exterior by his sojourn in the bowels of the Orient.

Duvivier’s Pépé le moko of 1937 offers us the tale of a French gangster who goes to ground in the casbah, represented in the film as an impenetrable space of multiracial, polyglot, feminized alterity. In Duvivier’s film, the dashing gangster Pépé is ultimately undone by his desire for a Parisian woman who penetrates into his lair in the casbah, suggesting that he has become unmanned despite his tough-guy exterior by his sojourn in the bowels of the Orient.

If the imperial gaze is both lured and repelled by the casbah, the increasingly powerful technologies of representation through which that gaze came to be deployed during the late colonial era present the titillating fantasy of penetrating the casbah’s labyrinthine streets in ever more realistic ways. Yet this realism was of course a construction, as the orientalistic excess of Pépé le moko underlines. Film, as Walter Benjamin suggested, might have been able to carve up reality like a surgeon, yet it hardly did so in a sanitized and objective manner.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZbfX3I_6VY]

Indeed, the scopophilic imperial gaze often substituted fantasies of technological penetration for the far less seemly modes of power assumed by colonial urban conquest and counterinsurgency. Gillo Pontecorvo’s great docudrama of the Algerian revolution, The Battle of Algiers, consciously juxtaposes these conflicting modes of urban biopower. The film opens with a torture scene in which the French paratroopers force a captive member of the Algerian resistance to confess the hiding place of the last remaining leaders of the liberation movement. Pontecorvo’s film then cuts to the opening credits, which unfold over scenes of the paras swarming through the streets and across the rooftops of the casbah.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4-jXauvPtjU]

The French ability to move effortlessly across the proscribed rooftops of the casbah and to penetrate into the private spaces of Algerian homes, the rest of the film demonstrates, is gradually developed and ultimately won through systematic practices of torture and summary execution that polarized French society and threatened the liberal regime of parliamentary rule that obtained in the metropole with the forms of authoritarian power articulated in the colony. Such blowback, Battle of Algiers implies, is the ineluctable outcome of imperial urban scopophilic fantasy.

How do representations of contemporary urban warfare compare with these colonial-era texts? Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down might be taken as a particularly paradigmatic example in this regard. Released in early 2002 as the US was preparing to invade Iraq, the film recreated the bruising defeat suffered by an elite group of Army Rangers at the hands of ethnic militias in Mogadishu in 1993. The film hammers home the message since repeated in great detail by theorists of Military Operations in Urban Terrain: war in cities is combat in hell. The scene in which the Rangers descend on the city from their remote base is particularly revealing.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbmdVlxIiy0]

The segueway from the preternatural calm of the troops as they approach the city in helicopters and the ensuing chaos on street level contrasts all too clearly with that other famous Hollywood representation of airborne assault: the “Ride of the Valkyrie” sequence from Apocalypse Now. Instead of an adrenalin-pumping soundtrack followed by the imbecilic orders issued to his surfing G.I.’s by the apparently invincible Lt. Col. Kilgore in Coppolla’s film, Black Hawk Down’s protagonists disappear into a sandstorm that literalizes the chaotic fog of war.

Yet if Black Hawk Down brutally reverses the gonzo heroism of Coppolla’s sequence and offers an unremittingly gory street-level depiction of urban warfare in the scenes that follow, it nevertheless shares a good deal with Vietnam revision films. Critics such as Susan Jeffords and Marilyn Young have argued that such films perform their ideological work by erasing the problematic political terrain of U.S. Cold War interventions.[xv] In films from The Green Berets (dirs. Ray Kellog and John Wayne 1968) to We Were Soldiers (dir. Randall Wallace 2002), the Vietnam War is transformed into a series of isolated battles of which Americans can feel proud through a recycling of World War II themes, with the crucial focus being on the combat troops themselves, the beleaguered “band of brothers” with whom the audience is encouraged to identify.[xvi] The tight focus on these noble warriors, almost always shown dying heroic deaths while clutching photos of loved ones, offers a strategic elision of political considerations of the war’s motives, and pits the lone soldier against not only hosts of enemies but also against the “Establishment” in the form of superior officers and the policy-making elite in Washington. True to this now-dominant form of Hollywood military myth making, Black Hawk Down sticks in many ways to the “support the troops” script. Despite a few scenes that raise concerns about the morality of the US military’s engagement in humanitarian interventions, the film retains a carefully circumscribed focus on citizen-soldiers under fire, a narrative thrust that leaves the viewer “in the position of vaguely distrusting government – a faceless, ambiguous ‘Washington’ – but embracing the military as embodied in the soldier-patriot – and thus, ironically, deferring to the decision-making of government institutions so as not to oppose the soldier culture that serves those institutions without question.”[xvii] Within the street-level perspective of the shooting and bleeding warband, there is quite literally no possibility of seeing through the eyes of the Somali other, who is depicted almost exclusively as a menacing horde.

Discussion of films depicting urban combat such as Black Hawk Down perhaps misses the mark, however, for such forms of representation have been to a significant extent replaced in the popular imperial imaginary by a new technology of scopophilia: the video game. Such games not only surpass film in terms of annual revenue, but in addition they have been taken on board by the military as an active tool not just for recruiting but also for training troops about to be deployed to urban combat zones.[xviii] It would be wrong to see videogames as antagonistic to cinematic technologies, however, since they build on and incorporate many of the key tropes of Hollywood representation. This should not be so surpring given the fact that, through outfits such as the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies, what James Der Derian calls MIME – the military-industrial-media-entertainment complex – has consolidated notable synergies between academia, Hollywood, and the military. Importantly, these video games vastly augment cinema’s claims to realism by allowing players not simply to look at a spectacle but to perform acts within the imaginary world conjured up through digital aesthetics.[xix] In fact, claims to fidelity of representation seem to be central aspects of the appeal of such games. During an era in which “embedding” prevented most members of the American public from gaining access to representations of the battle zones in Iraq and Afghanistan, videogames produced either by the US military or through the many cooperative agreements that characterize the burgeoning military-entertainment complex offered privileged glimpses of the predominantly urban battlefields of the War on Terror.

One of the most successful of these videogames is America’s Army. Developed using $7 million of taxpayer money, the game was made available for free on an Army website and was downloaded 2.5 million times during the two months following its release.[xx] The game theoretically takes players through strenuously accurate versions of the Army’s basic training program that include training in military operations in urban terrain (MOUT), allowing successful players to graduate eventually to Special Forces operations in combat zones. Promotional material for the game, which also serves quite openly as an Army recruitment drive, stresses the verisimilitude of the game by ironically blurring the dividing line between reality and the game, suggesting that warfare has become a totally cybernetic experience.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWtzE8Y60io]

Yet, just as was true in cinema, this imperial cybernetic technology interpolates subjects in a particular manner. The first-person shooter format of the game reduces urban spaces to free fire zones. Game players are always positioned as American or British troops. When groups of networked players battle one another, each team sees their antagonists through a form of cybernetic Orientalism, their opponents’ skin tone magically rendered more swarthy and their upper lips sporting Saddam-style mustaches. The feeling of interactivity and somatic immersion programmed into the game thus creates an illusory experience of realism since the game always reproduces the dominant ideological orientation of the current policy establishment. No consideration is given to the broader ethical questions raised by warfare in the name of fostering democracy, and there is little opportunity within the space of the game to consider the impact of war on civilians or on the long-term psychological health of combatants. The more such games emphasize contextual detail, the more glaring is the discrepancy between such gestures towards verisimilitude and the streamlined and endlessly reproducible character of the first-person shooter game on which they are all modeled. This contrast is particularly stark in a game like Kuma\War, whose website regularly features updated mini-scenarios grounded in specific events in the War on Terror, with abundant journalistic back stories and detailed testimony from members of the Armed Forces to support the game’s realism, but which ultimately devolves into first-person shooting matches.

While screening out the contradictions of urban warfare, post-9/11 video wargames emphasize bonding through combat in a manner analogous to and perhaps more powerful than that of cinematic relations of theirs such as Black Hawk Down. The game Full Spectrum Warrior, whose title archly refers to JFCOM’s doctrine of supremacy on multiple different levels of the battlezone, hinges on precisely such male bonding. The game begins with two squads – Alpha and Bravo companies – dropped off like the Rangers in Black Hawk Down in the midst of a city filled with hostile fighters and cut off from their commanders by the static of war. Players must leapfrog their teams through dangerous city streets.

What unfolds in the game is an intense homosocial fantasy, one in which the soft flesh of the enemy is the medium through which video war-gamers achieve immortality by bonding with a band of brothers and by freezing time in the eternal present of the gaming battlezone.[xxi]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DZILu5jiUF4]

None of the video games I have discussed attempt to hide the bloody character of urban war; instead, the thanatopoetic performance of the war-gamer is an extension of the erotomaniac gaze of the colonial scopophiliac. There are few women present in these games, civilian or otherwise, and none of the eroticized objects that attracted the colonial gaze. Instead, the city itself is turned into a plastic, feminized body, to be swarmed over and penetrated at will by the cybernetic warrior. There is, I would argue, a strong link between the repetition compulsion of cybernetic death dealing in games like Full Spectrum Warrior and the desire for eternal life that characterizes the ambivalent drives of the imperial imaginary across the colonial-postcolonial divide. War games literally provide an intoxicating opportunity for players to live out General Westmoreland’s fantasy of fully automated warfare, creating a space in which death can be overcome through the cybernetic extension of the self into an eternal imperial future.

Although Full Spectrum Warrior locates its players in the chaotic spaces of global cities of the South, the vertical axis of the imperial gaze always beckons. When either of the squads gets particularly badly pinned down by enemy fire, for example, team leaders/players can use GPS to survey the area and, when things get really hectic, can call in helicopter reconnaissance and bombardment. At these moments in the game, as the vertical axis of imperial vision reasserts itself, players adopt the perspective of what Jordan Crandall calls “a militarized, machinic surround,” an angle of vision involved in “positioning, tracking, identifying, predicting, targeting, and intercepting/containing.”[xxii] The fantasy here is of a militarized cyborg identity in which the horizontal and verticle axes of imperial vision blend seamlessly together. The libidinal tug of this form of what Crandall calls “armed vision” is strong. As he puts it, “One cannot underestimate the extent to which representation, cognition, and vision are embedded within this circuit. The drive is bound up in an erotic imaginary of technology-body-artillery fusion, fueled under the conditions of war.”

Yet as critics such as Stephen Graham and P.W. Singer have argued, the dreams of technological mastery that animate Pentagon robotic technologies such as the Predator drone program raise dramatic practical and ethical questions.[xxiii] On the most immediate level, they tend to turn warfare into a bloodless video game, deadening US warfighters’ sensibilities to killing and incensing target populations, as even the generals seem willing to admit. In addition, as armed robots become increasingly autonomous, particularly thorny issues concerning agency, responsibility, and violence arise. As the philosopher Peter Asaro argues, new legal regimes need to be developed to ban autonomous military robots since it is impossible to determine ultimate responsbility for war crimes committed by such weapons. Finally, many technologies of robotic destruction, like IEDs, are relatively inexpensive and easy to manufacture. Unless the desire for technological mastery that characterizes the vertical axis of the imperial urban gaze is checked, it is only a matter of time before such robots become as ubiquitous and deadly as landmines for everyone in (and even outside) combat zones.

The massive growth of the global cities of the South over the last quarter century and the increasing prevalence of warfare in these cities has made the technophilic fantasies of robowar very attractive for the contemporary imperial imaginary. As I have tried to demonstrate, however, these desires and the visual economy that supplements and underpins them did not emerge out of thin air. Although the question of urban empire today is connected to networked digital warmaking technologies, these issues are never simply technological but are rather deeply embedded in visual economies and imaginaries with a long imperial history. Moreover, the genealogy of the imperial urban visual economy that I have traced by looking at representations of colonial Calcutta and Algiers underlines the extent to which the spectacular architecture of imperial urbanism was always shot through with an unstable mixture of fear and desire. The inescapable propinquities of the imperial city ensured, in other words, the mutability of identity in the urban realm, rendering strategies aimed at constructing condons sanitaire of various forms futile in the long run.

The same might be said for contemporary imperialist military operations in urban terrain, for although such operations may produce tactical successes, they almost inevitably generate broader strategic debacles. Even contemporary Pentagon operatives seem willing to admit this fact. Six months after the start of the Iraq War, for example, the special operations chiefs at the Pentagon organized a screening of Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers for their employees that sought to highlight the pitfalls of attempts to stamp out urban counter-insurgencies. The flyer for the screening set out the parallels between the battle of Algiers and urban conflicts in contemporary Iraq quite clearly: “How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas… Children shoot soldiers at point blank range. Women plant bombs in cafes. Soon the entire Arab population builds to a mad fervor. Sound familiar? The French have a plan. It succeeds tactically, but fails strategically. To understand why, come to a rare showing of this film.”[xxiv] One can’t help thinking that the Pentagon could have used a few more screenings of The Battle of Algiers.

[i] Jay Reist, quoted in USJFCOM press release, “FITE demonstration builds small unit teamwork, cohesion,” Accessed 3/21/11, http://www.jfcom.mil/newslink/storyarchive/2010/pa092010.html

[ii] The doyen of US military theorists, Andrew Marshall of the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment, notes that the Soviets were the first to begin speculating about the impact of information technology on warfare, although it was his legendary memorandum of 1993, “Some Thoughts on Military Revolutions,” that triggered the full blown discourse on a revolution in military affairs within the US. See James Der Derian, Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network (Boulder, CO: Westview, 2001), 28.

[iii] Ed Halter, From Sun Tzu to Xbox: War and Video Games (New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 2006), 103.

[iv] James Der Derian, Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network (Boulder, CO: Westview, 2001), xv.

[v] Swati Chattopadhyay, Representing Calcutta: Modernity, Nationalism, and the Colonial Uncanny (New York: Routledge, 2006), 9.

[vi] Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject, 18.

[viii] King, Anthony D., Colonial Urban Development: Culture, Social Power and Environment (London: Routledge, 1976), 142.

[ix] Zeynep Çelik, Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers Under French Rule (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997).

[x] On the miasmic theory of disease, see Sheldon Watts, Epidemics and History: Disease, Power, and Imperialism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999). For discussion of the role of the miasmic theory of disease in the colonial urban development of New Delhi, see Anthony J. King, Colonial Urban Development.

[xi] For a discussion of Foucault’s notions of biopower, neoliberalism, and warfare, see Leerom Medovoi, “Global Society Must Be Defended: Biopolitics Without Boundaries,” Social Text 91 (vol. 25, no. 2, Winter 2008): 53-79.

[xii] Cited in Çelik, 15.

[xiii] For more extensive discussion of Delacroix’s painting, see Assia Djebar, Women of Algiers in their Apartment (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1999).

[xiv] See Malek Alloula, The Colonial Harem (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 1986).

[xv] Susan Jeffords, The Remasculinization of American Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989); Marilyn B. Young, “In the Combat Zone,” Radical History Review 85: 253-64.

[xvii] Stephen A. Klien, “Public Character and Simulacrum: The Construction of the Soldier Patriot and Citizen Agency in Black Hawk Down,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 22.5 (December 2005): 444.

[xviii] On video game sales, see Halter, xviii.

[xix] On the realist aesthetic in videogames, see Alexander Galloway, “Social Realism in Gaming,” Game Studies 4.1 (November 2004), accessed September 25, 2009, <http://gamestudies.org/0401/Galloway>.

[xxi] On Full Spectrum Warrior in particular and imperial video gaming in general, see Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter, Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 97-123.

[xxii] Jordan Crandall, “Armed Vision,” Multitudes 15 (May 2004).

[xxiii] Stephen Graham, Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism (New York: Verso, 2010) and P.W. Singer, Wired for War: The Robotic Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century (New York: Penguin, 2009).

[xxiv] Cited in Charles Paul Freund, “The Pentagon’s Film Festival: A Primer for The Battle of Algiers,” Slate (Wednesday, August 27, 2003), accessed February 11, 2008, <www.slate.com.>

Yesterday I saw Allan Sekula and Noel Burch’s powerful film The Forgotten Space. The idea behind the film is that the sea is a space which we have come to see as nothing other than a blank surface across which vast quantities of goods can be transported in nondescript shipping containers. If we once revered the sea as a consumer of souls, today we are killing it through acidifying carbon emissions from the thousands of gigantic container ships that ply the waters of the world.

Yesterday I saw Allan Sekula and Noel Burch’s powerful film The Forgotten Space. The idea behind the film is that the sea is a space which we have come to see as nothing other than a blank surface across which vast quantities of goods can be transported in nondescript shipping containers. If we once revered the sea as a consumer of souls, today we are killing it through acidifying carbon emissions from the thousands of gigantic container ships that ply the waters of the world. Rotterdam, Los Angeles, Hong Kong, and Bilbao. Through interviews and haunting vignettes in each of these maritime sites and their hinterlands, Sekula and Burch show how containerization has facilitated the globalization of production while also dismantling unionized labor forces in the developed world. The result is been sweeping generation of what Zygmunt Bauman calls wasted humanity: people and places for whom the neoliberal economy no longer has any practical use.

Rotterdam, Los Angeles, Hong Kong, and Bilbao. Through interviews and haunting vignettes in each of these maritime sites and their hinterlands, Sekula and Burch show how containerization has facilitated the globalization of production while also dismantling unionized labor forces in the developed world. The result is been sweeping generation of what Zygmunt Bauman calls wasted humanity: people and places for whom the neoliberal economy no longer has any practical use. impoverished countries, and then staff them with an ill paid and eminently disposable labor force from underdeveloped nations such as the Philippines.

impoverished countries, and then staff them with an ill paid and eminently disposable labor force from underdeveloped nations such as the Philippines. resilience. So we see workers around the world finding ways to retain a sense of individual dignity and collective identity despite the often grueling conditions under which they work.

resilience. So we see workers around the world finding ways to retain a sense of individual dignity and collective identity despite the often grueling conditions under which they work.