Survival is our politics now. So says French political anthropologist Marc Abélès in The Politics of Survival. And so say many cultural producers today, although this admission often comes by way of what cultural theorist Fredric Jameson called the political unconscious more than through any overt acknowledgement of the true character and gravity of the crises we confront today.

Survival is our politics now. So says French political anthropologist Marc Abélès in The Politics of Survival. And so say many cultural producers today, although this admission often comes by way of what cultural theorist Fredric Jameson called the political unconscious more than through any overt acknowledgement of the true character and gravity of the crises we confront today.

Take Ridley Scott’s recent film Prometheus, for example. The film is a prequel to Alien (1979), a film which shared a great deal in common with previous Cold War-era paranoid movies such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bEVY_lonKf4]

Of course, Alien was a film of its time. The movie’s focus on the biopolitical threat of contagion was clearly influenced by the ecological crisis of the 1970s and by previous works of biopolitical horror such as Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain (1969). In addition, the bad-ass heroine Ellen Ripley was very much a product of second-wave feminism.

Nonetheless, just as in earlier films of paranoid American empire such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Scott’s Alien features a hapless crew of (multicultural but clearly American) explorers who stumble upon an alien horde that subsequently annihilates them. The message seems to be that the expansion of U.S. capitalism can bring its agents – the crew members of the spaceship Nostromo (in a nice reference to Joseph Conrad) are bringing a freight of iron ore back to Earth – into contact with threatening populations of aliens. But it is the survival of this small group of explorers alone that is at issue.

Contrast this with Prometheus. In Scott’s prequel, released thirty three years after the original, it is the survival of humanity itself that is at stake.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1byZkbNB3Jw]

In Prometheus, we find out that the aliens which Ripley battled are the product of a toxic biological weapon engineered by a race of god-like extraterrestrials who, having created humanity, have now decided to wipe us out for some inexplicable reason. The struggles of archeologist Elizabeth Straw to survive the various alien threats that assail her thus stand in for the struggle of humanity itself to stay alive.

One could perhaps say that the inscrutable motives of the “Engineers” who created us and now seem bent on our destruction in Prometheus might stand in for our planet’s environment, which seems to be turning against us with increasing virulence and unleashing multiple unanticipated plagues upon us. This is perhaps stretching allegory a bit far, but the crux of the film is indisputably the struggle for species survival, a marked shift from the earlier Alien films.

The obsession with survival in contemporary U.S. culture is virtually inescapable. Soon after seeing Prometheus, I wandered into Amie Siegel’s exhibition Black Moon (2012) in the Austin Museum of Art. Siegel’s video installation offers a powerful evocation of the current obsession with apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic scenarios. Long panning shots through blighted suburban housing developments in what appears to be Phoenix or some other city of the Southwest evoke the sub-prime mortgage-fueled bust.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MySAWhkN1pA&feature=youtu.be]

Erupting into this bleak landscape of politically engineered economic abandonment, a small band of women guerrillas struggles to survive an unnamed and invisible nemesis.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DoprhIeTj0k&feature=youtu.be]

Like Scott’s Prometheus, Siegel’s video exhibition remixes an original from the 1970s, in this case Louis Malle’s film Black Moon. Siegel’s piece updates the original, though, by situating the unexplained civil war in the context of neoliberal blight. Like Scott’s film, Siegel’s work also focuses on women as protagonists. The exhibition shares a great deal with Sarah Hall’s dystopian novel The Carhullan Army (2007), in which a commune of radical feminists takes to the Scottish highlands in order to survival the ecologically driven collapse of modern society.

This kind of apocalyptic narrative exerts such as strong appeal on the contemporary political unconscious, I want to argue, precisely because of the absence of genuine acknowledgement of the gravity of the crises that confront us in mainstream discourse.

The exhaustion of the neoliberal model of capitalism has been addressed by elites since the onset of the present crisis in 2008 by wave after wave of heightened austerity that is doing nothing but exacerbating the crisis, as well as drowning average people in misery. The political systems in both the U.S. and E.U. seem gripped by total gridlock, with rule being carried out in Europe by conservative bankers whose feckless measures have plunged the economic union into interminable crisis. Meanwhile, in the U.S., a political system riddled with corruption as a result of the influence of big money has spiraled into previously unknown extremes of partisanship and polarization. And, of course, underlying these crises, we continue to push the planet through incremental increases in carbon emissions into a climate crisis from which there is likely to be no exit for the vast majority of humanity.

There is, of course, little substantial admission of these crises in mainstream discourse, let alone an attempt to grapple with the kind of serious, systemic transformations that would be necessary in order to stem our current headlong rush towards oblivion.

Given this fact, the apocalyptic political unconscious proffered by films such as Prometheus can often seem very attractive. Hell, at least someone is willing to admit we’re in deep shit.

There are, nonetheless, significant dangers associated with such an outlook. As Eddie Yuen and the other contributors to the forthcoming volume Catastrophism point out, apocalyptic thinking distorts our understanding of the organic crisis faced by contemporary civilization. As a result, such thinking more often impedes rather than fuels progressive responses to crisis. In fact, if catastrophism has any basic DNA, it is in the apocalyptic thinking of fundamentalist religious movements, which tend to be animated in their responses to crisis by highly reactionary social mores.

The challenge we face, then, is to survey and help the multitude understand the depth of the crisis we currently face, while not giving in to apocalyptic rhetoric. We cannot afford to wait for the slate to be wiped clean before we build new, sustainable societies. That battle has to be waged in the present, through initiatives both pragmatic and visionary enough to engage people in genuine campaigns of hope.

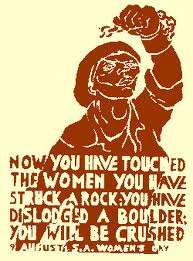

Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo’ – You Strike a Woman, You Strike a Rock. This slogan has come to define the struggle of women against oppression in South Africa. The rallying cry originates in a 1956 march led by women against the apartheid regime’s odious pass laws, which controlled the movement of people of color within the country.

Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo’ – You Strike a Woman, You Strike a Rock. This slogan has come to define the struggle of women against oppression in South Africa. The rallying cry originates in a 1956 march led by women against the apartheid regime’s odious pass laws, which controlled the movement of people of color within the country. Indigenous women from Guatemala talked, for example, about having to walk for 2-4 hours per day in order to retrieve water for domestic use since extractive mining operations in their communities are consuming the lion’s share of public water supplies. An activist from Colombia talked about the often-violent displacement of women by the “green grabbing” activities of large-scale agrofuel production companies. Linking violence against women’s bodies with structural economic forms of violence, a woman from Fiji underlined the necessity of thinking (and mobilizing) across different scales.

Indigenous women from Guatemala talked, for example, about having to walk for 2-4 hours per day in order to retrieve water for domestic use since extractive mining operations in their communities are consuming the lion’s share of public water supplies. An activist from Colombia talked about the often-violent displacement of women by the “green grabbing” activities of large-scale agrofuel production companies. Linking violence against women’s bodies with structural economic forms of violence, a woman from Fiji underlined the necessity of thinking (and mobilizing) across different scales.