Woeburn Tenzin presented on Tibet as the third pole of the world because of all of the glaciers there. She is a member of the organization Tibet Third Pole.

Woeburn Tenzin presented on Tibet as the third pole of the world because of all of the glaciers there. She is a member of the organization Tibet Third Pole.

She showed photographs of the retreat of glaciers in Tibet as a result of climate change. The result is the formation of huge glacier lakes.

She also showed charts of temperature rises in Llahsa, resulting in shorter seasons. There’s also a rise in permafrost temperatures. As a result, deserts are taking over the grasslands that formerly were sustained by water in the permafrost.

The most terrifying factor she underlined was the fact that glaciers in Tibet contribute to the following rivers: Indus, Brahmaputra, Yellow, Mekong, Yangtse. Basically, the rivers that provide drinking water for a very significant portion of humanity. The Mekong River, for example, supports 70 million people from Tibet to Vietnam. Here’s a useful article that summarizes the seriousness of the impact on rivers.

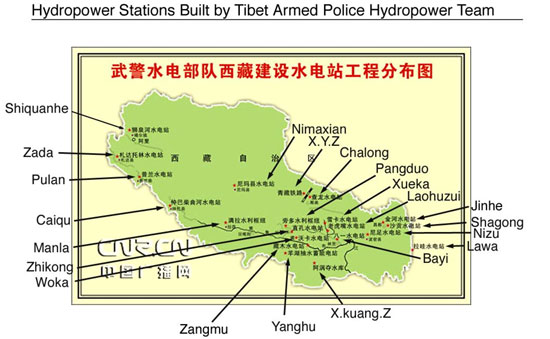

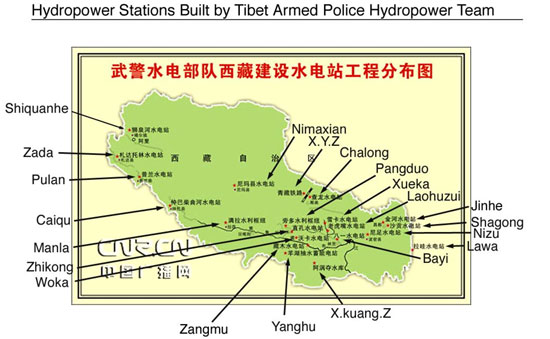

China is reacting by building dams on many of these rivers to harness hydro-electric power. Hundreds of dams. But when you build dams, you displace people and add to water evaporation.

Construction of the Three Gorges Dam displaced up to a million people, for example. China has bigger dams in mind.

What impact will all of these dams have on the nations downstream?

Woebum then screened a brief film called Meltdown in Tibet that provides narration and images for some of the problems she described. Behind frantic dam building, 70% of China’s lakes are polluted. Its dream is to divert water from Tibetan plateau to provide for its water-starved cities. This is the largest dam-building engineering project ever undertaking.

After Woebum Tenzin’s presentation, Payal Parekh, an expert on climate change and dams, spoke. She drew on research done by the organization International Rivers. There are a host of problems with dams, she argued:

- displacement of communities: estimates are that approximately 40 million people around the world have been displaced by dams

- reduced water quality and quantity

- loss of habitat: dams have major impacts on wildlife habitat, often leading to widespread extinctin

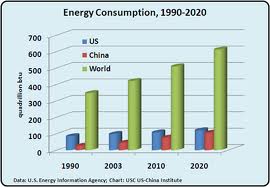

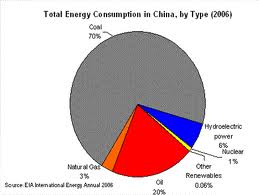

Why is China building so many dams?:

- Energy for mining and prospecting

- infrastructure development

- power for urban China – China is plagued by major energy shortages

- promotion of rapid development in Tibet (although this isn’t to benefit Tibetans)

- diversion of water

Dams are based on historical data about river flow, but climate change means that such predictions are not reliable. More extreme weather events are expected.

Someone in the audience explained that China is not the only country building dams: India is planning on building nearly 160 dams, trying to preemptively get access to the water that China is trying to access.

Better solutions exist that diversify and decentralize energy production. These solutions aren’t easy, but they are better than the massive amount of dam building contemplated around Tibet. Unfortunately, though, dams are being brought back by elites as a solution to the climate crisis. We need to struggle against this on international level and on local level.

There is a tendency among critics in the growing Energy Humanities camp to focus almost exclusively on the symbolic politics (and geopolitics) of petroleum. This reflects, I think, the way that the current dominant mode of resource exploitation shapes our consciousness, regardless of differences of time and space.

There is a tendency among critics in the growing Energy Humanities camp to focus almost exclusively on the symbolic politics (and geopolitics) of petroleum. This reflects, I think, the way that the current dominant mode of resource exploitation shapes our consciousness, regardless of differences of time and space. modes of production and outmoded moves of working class organizing in the developed world.

modes of production and outmoded moves of working class organizing in the developed world.