Following on my last post concerning the danger of reproducing the dismal logic of contemporary capitalism in representations of uneven development, this morning I began thinking about the question of what we communists want.

Part of the problem in trying to think this question today is that utopian horizons have been smashed and discredited by the patent failures of “really existing” socialism around the world during the last half century. But another strong problem is the way in which capitalism has gotten under our skin and into our minds, defining what is possible.

Part of the problem in trying to think this question today is that utopian horizons have been smashed and discredited by the patent failures of “really existing” socialism around the world during the last half century. But another strong problem is the way in which capitalism has gotten under our skin and into our minds, defining what is possible.

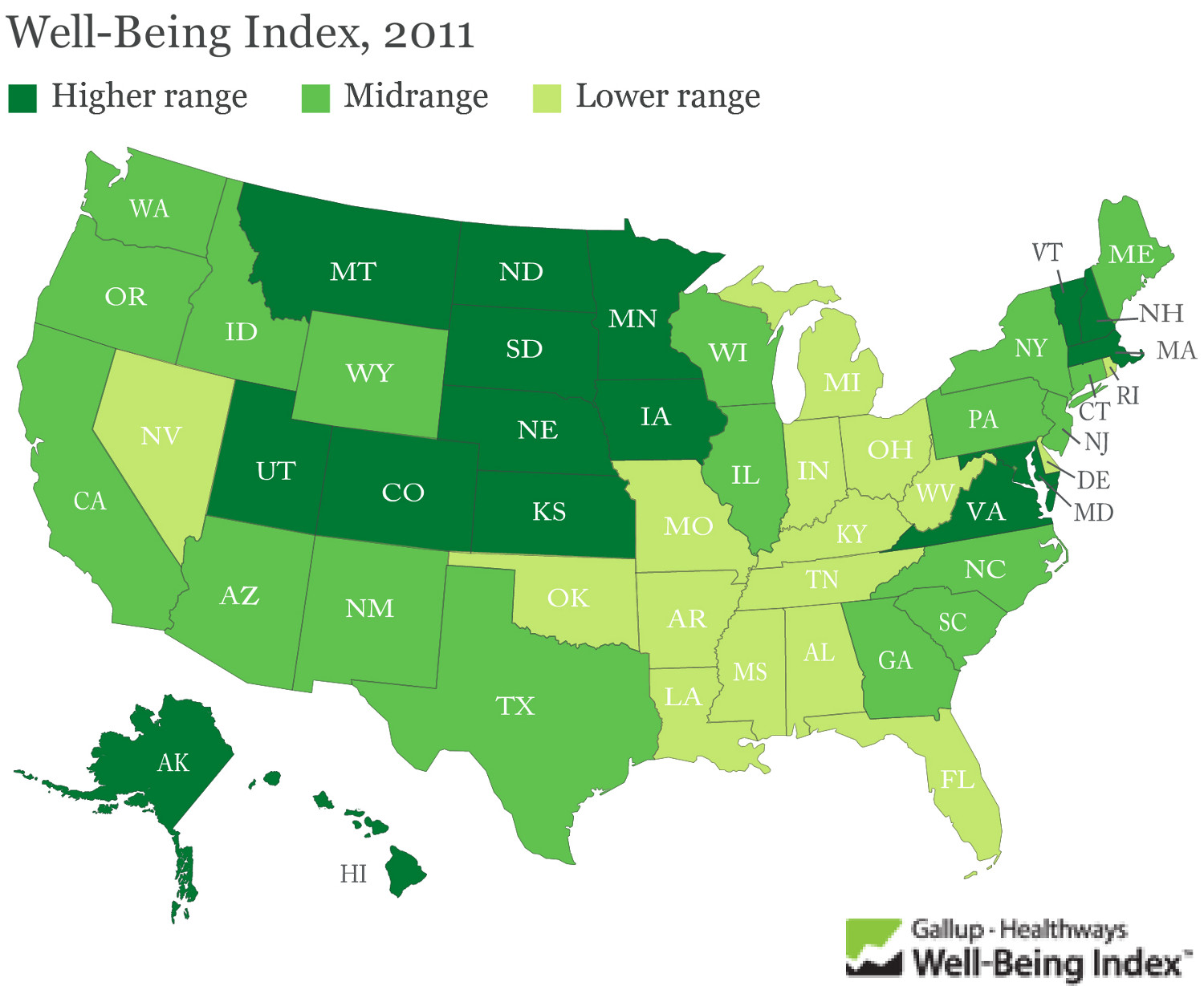

So, if we’re going to insist that another world is possible, what kind of world do we want it to be? Certainly not the one we currently inhabit. The New Economics Foundation (NEF) has been doing a great deal of work on the issue of Well Being. Two key facts they mention: since 1970, the UK’s Gross Domestic Product has doubled, but people’s satisfaction with life has not changed; 81% of Britons believe the government should prioritize creating the greatest happiness rather than the greatest wealth.

The NEF has participated in some important attempts to redefine Well Being on a national and international level, shifting the conversation away from GDP, which, as they point out, can be augmented through increased sales of guns and tobacco just as much as through increased spending on education and child care facilities. The projects of theirs that are worth checking out: Happy Planet Index (the “leading global index of sustainable well being) and the National Accounts of Well Being project.

Part of the problem here is that prescriptions for well being can often come across as pretty banal. NEF’s Five Ways to Well Being thus includes a list of actions that seem pretty obvious:

- Connect

- Be Active

- Take Notice

- Keep Learning

- Give

They also seem hopelessly oriented to middle class citizens of affluent, overconsuming nations of the global North. It makes sense on some level to target such hyperconsumptionist subjects since the materialistic values that we Northerners have been coaxed to embrace are at the leading edge of destroying the planet through anthropogenic climate change, and our materialism is being disseminated through the global media as the paradigm to which all developing countries should aspire. We have to shift values in the global North if we are to avert catastrophe.

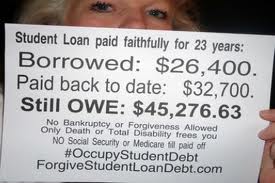

We also need to dismantle the skein of false desires generated by capitalist culture. This has been a dominant preoccupation of the Left over the last century, from the Frankfurt School intellectuals’ dyspeptic critiques of consumer culture, to Thomas Frank’s more recent discussion of the rise of Right-wing sentiments among the U.S. working class in books like What’s Wrong With Kansas?, to Sara Ahmad’s The Promise of Happiness, which discusses the ways in which the imperative to be happy leads to straightened and oppressive definitions of the self and social being.

Despite, then, the importance of this discussion of alternative definitions of well being in the North, it’s important to simultaneously ask what the question of well being would look like from a global South perspective. A partial answer to this question is given in the Vivir Bien project. Growing out of the insurgent Bolivarian movement in Latin America, the project is explicitly anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist.

An immediate set of demands on the path to well being were articulated at the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth. The People’s Agreement crafted at this conference in Bolivia includes the following demands:

- harmony and balance among all and with all things;

- complementarity, solidarity, and equality;

- collective well-being and the satisfaction of the basic necessities of all;

- people in harmony with nature;

- recognition of human beings for what they are, not what they own;

- elimination of all forms of colonialism, imperialism and interventionism;

- peace among the peoples and with Mother Earth;

I’d be very interested to hear what kinds of other models of well being have been articulated by social movements around the globe in recent years. At the beginning or the end of these lists, of course, should come the abolition of capitalism and its drive to ceaseless accumulation, which is of course at the roots of everyone’s unhappiness as well as the threat of planetary extinction.