Last night the British movie The King’s Speech won big at the Oscars. I didn’t watch the ceremonies, but I wonder whether the irony was apparent in the festivities: while dictators are toppled, often at the cost of many lives, throughout the Middle East, the Angl0-American establishment is engaged in full-throated celebration of monarchy.

Last night the British movie The King’s Speech won big at the Oscars. I didn’t watch the ceremonies, but I wonder whether the irony was apparent in the festivities: while dictators are toppled, often at the cost of many lives, throughout the Middle East, the Angl0-American establishment is engaged in full-throated celebration of monarchy.

Of course, King George VI, the stuttering protagonist of The King’s Speech, was no Louis XIV. The film demonstrates his human qualities; indeed, his battle to overcome a speech impediment in order to rally Britain in the face of Hitler’s onslaught makes his body into a metaphor of the British body politic in general. This is a trope that goes back to Shakespeare’s time, and that evidently continues to resonate.

And part of the drama of the film derives from the King’s need to overcome his inherited superciliousness enough to trust the Aussie speech therapist who “cures” him of his stuttering.

In depicting George VI’s struggles, The King’s Speech participates in a trend evident since the days of Princess Diana towards humanizing the British monarchy (and aristocracy more broadly). Stephen Frears’s film The Queen managed to perform similar work for Queen Elizabeth, who had previously been famous to cold-shouldering Diana into her grave.

Of course the king’s struggle to overcome fears he seemingly inherited from the tyrannical atmosphere created by his father is powerful. But I think there’s something deeply pernicious about the film, nonetheless. Of course, if you’re going to be ruled by a monarch, it’s best that that they identify with the people and have their powers limited constitutionally. However, there’s nothing particularly benign about the British monarchy. They absorb millions of pounds worth of public funds every year, at a time when budgets for education, libraries, and all sorts of other public institutions are being slashed. As Tom Nairn demonstrates powerfully in Enchanted Glass, Britain’s enduring infatuation with the monarchy prevents it from constructing many of the significant democratic institutions of a true republic.

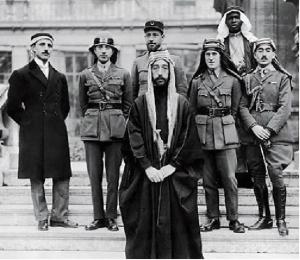

In addition, we shouldn’t forget the history surrounding World War II, upon which The King’s Speech turns. The British monarchy never explicitly sided with the Nazis, but there was much pro-fascist sentiment among the British aristocracy in the 1930s. Britain refused to side with democracy in Spain when Franco’s fascist forces began their campaign. Moreover, during this period, Britain helped establish some of the more pernicious dictatorships of world history, including the House of Saud (pictured above).

The King’s Speech is a symptom of the enduring appeal of imperial/royal nostalgia today. In a moment in which there is so much visceral public anger against the democratic welfare state, our culture industries nonetheless churn out paeans to national unity in the solitary figure of the “good” monarch. What about a film about what happened to the working class kids who were displaced by the Blitz, and whom middle class Britons often turned out of their homes? Enough with the sordid heritage industry already!