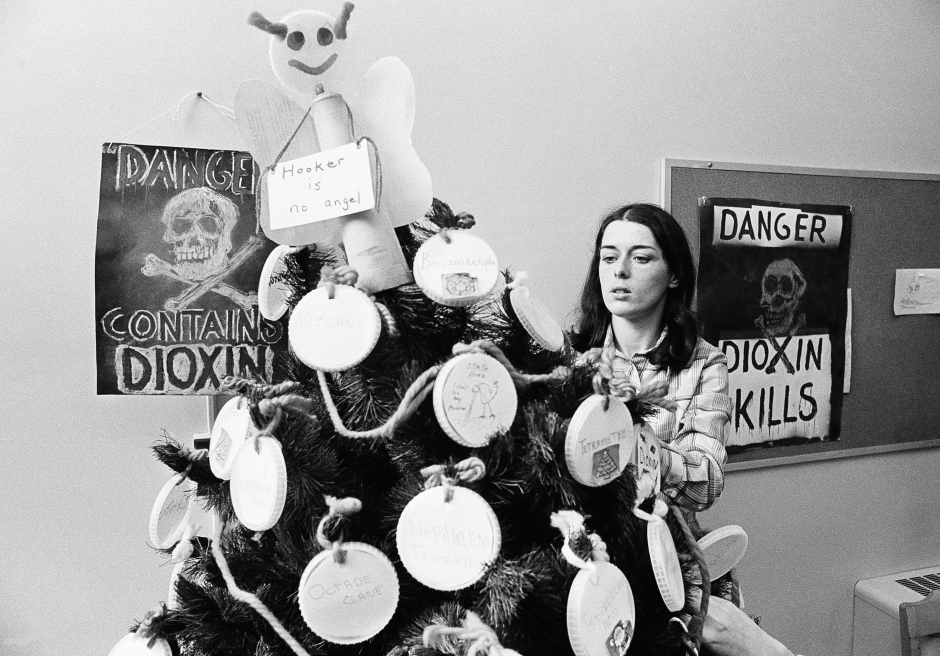

While surfing the web recently I came across a really nice article on Lois Gibbs, the founder of the Center for Health, Environment, and Justice, and one of the primary protagonists of the battle against the poisoning of a working class community at Love Canal in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

While surfing the web recently I came across a really nice article on Lois Gibbs, the founder of the Center for Health, Environment, and Justice, and one of the primary protagonists of the battle against the poisoning of a working class community at Love Canal in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Gibbs and her friends fought against lying chemical companies and conniving government bureaucrats. They even held two members of the EPA hostage in order to get the attention of President Carter.

Their story is a key one in the annals of the US environmental movement, but it’s not nearly well known enough. In fact, it seems to me that the environmental movement in general is not nearly as well remembered as contemporaneous movements such as feminism and civil rights. Why is this?

Perhaps it has to do with the different institutional impacts of these movements. I’m generalizing wildly here, but it could be said that the environmental movement achieved a string of political victories that led to the creation of government organizations such as the EPA and inside the beltway NGOs like the Natural Resources Defense Council. It quickly stopped being an insurgent grassroots movement, and made little impact on enduring Leftist enclaves such as academia.

By contrast, feminism and civil rights both established toe holds in US universities through women’s studies, Black and Latin@ studies programs, and remained more organically linked to grassroots struggles (even if this sometimes was a result of problematic identity politics). In fact, it took a fusion of civil rights and environmental struggles to kickstart a more grassroots avatar of environmentalism in the 1980s: the environmental justice movement.

These reflections are far less accurate when one turns to environmentalism in the global South. As Ramachandra Guha and Rob Nixon have shown, environmental movements in the South are generally linked far more closely to struggles to preserve the commons and to survive than those in the North. Nonetheless, the history of movements such as the Chipko anti-logging protesters in India and the rubber tappers in Amazonia are not very well recorded.

Thinking about Lois Gibbs made me wish there was more public awareness of the history of environmentalism, both within the US and globally. While looking through online materials linked to Gibbs, I came across the trailer for a new film, A Fierce Green Fire, that seeks to tell precisely such stories. It is, the producers claim, the first big picture exploration of the environmental movement, and it was just released. Pretty hard to believe that it’s taken this long!

Here’s the trailer for the film:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bc40_9tVUao]