Today the Democratic Left Front, a new formation in South African politics, organized a conference on Ecosocialism.

The conference began with a youth delegation arriving on the wings of rousing anti-apartheid choral singing:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrsnAPnnTCI&feature=mfu_in_order&list=UL]

There was some difficulty getting the conference going because the singers kept their kinetic chants wheeling round. Makes sense. To sit down and listen is to give up a kind of agency, often to speakers who are older, wealthier, and whiter than they. Sitting here at the beginning of this program, I wonder to what extent the organizers have erred in not including more space for these young people in the conference. But perhaps there will be opportunity for dialogue of some kind during Q&A.

Michelle Maynard of the Pan-African Climate Justice Alliance began the day by talking about the links between human beings and all of the natural systems on the planet. She went on to contrast this with the reified view of the Earth promoted by the Enlightenment and the scientific revolution. Maynard then continued to talk about how this worldview underlies current attitudes towards the commodification of the planet.

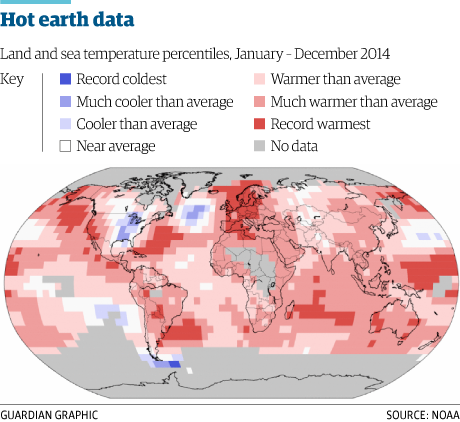

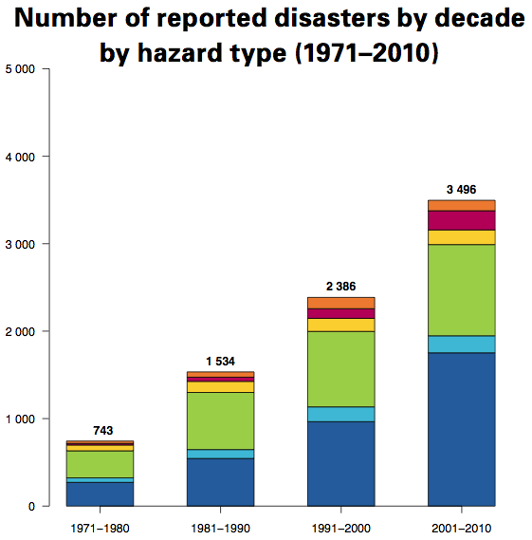

Next up, Vishwas Satgar spoke about the need to have this conference in order to arm the comrades against neoliberalism. This kind of capitalism is about chaos, since it is driven by unstable financial speculation. What we’ve seen in past decades in global South and what we’re seeing now in heartlands of capitalism today is global instability of neoliberalism. But capitalism is not surrendering. The current financial crash doesn’t mean that capitalism is dead. In the end, the squeeze is on all of us. We have to pay the price of paying the debts of capitalism, just as nature gets squeezed. Other legs of systemic crisis: food crisis resulting from systemic control of food by capitalist corporations, leading to major hunger crises around world; resource peaks, including oil, and the scramble for what’s left, as two most populous countries of the world – China and India – scramble for more scarce resources; climate change, and resulting political chaos, leading us into increasingly dangerous period politically; securitization of political life.

driven by unstable financial speculation. What we’ve seen in past decades in global South and what we’re seeing now in heartlands of capitalism today is global instability of neoliberalism. But capitalism is not surrendering. The current financial crash doesn’t mean that capitalism is dead. In the end, the squeeze is on all of us. We have to pay the price of paying the debts of capitalism, just as nature gets squeezed. Other legs of systemic crisis: food crisis resulting from systemic control of food by capitalist corporations, leading to major hunger crises around world; resource peaks, including oil, and the scramble for what’s left, as two most populous countries of the world – China and India – scramble for more scarce resources; climate change, and resulting political chaos, leading us into increasingly dangerous period politically; securitization of political life.

What’s at the heart of all of this is inability of a civilization to reproduce itself. In this context, what are the ruling classes offering us? What are they putting on the table? They’ve been talking about addressing the climate crisis through markets. Clean development mechanisms, green markets, Kyoto Protocol, etc. – all these solutions embed the market as center piece. These are all master concepts of green neoliberalism today. All of these solutions are still married to juggernaut of growth and industrialization. But we’re at the point where crisis is total. We can’t fix the crisis through piecemeal solutions such as decarbonization using markets. We need a total solution. Marketization is also about competitive strategies: taking crisis and turning it into an opportunity for more accumulation. We know that commodification creates enclosures. Green economy does not address the deeper systemic crisis.

In response to this civilizational crisis, we need resistance. We’ve been living through upswing of resistance over past two decades.  Chiapas, Egypt, Occupy Wall Street. But this resistance has to go further. It has to be civilizational resistance. We also need to transnationalize alternatives. The dominant view is that we’re an irrational mob. But we have answers and alternatives, and we need to put them forward on transnational level. COP17 isn’t going to solve the problem. The battle is in particular national contexts. We need to take the battle forward on this level.

Chiapas, Egypt, Occupy Wall Street. But this resistance has to go further. It has to be civilizational resistance. We also need to transnationalize alternatives. The dominant view is that we’re an irrational mob. But we have answers and alternatives, and we need to put them forward on transnational level. COP17 isn’t going to solve the problem. The battle is in particular national contexts. We need to take the battle forward on this level.

Jacklyn Cock, Professor at University of Witwatersrand, then spoke about how capitalism is responding to the current crisis. Capitalism is responding by saying that it doesn’t have to change. It can adapt through three key techniques: new technology, like carbon capture & storage and GMO crops, which have not been adequately tested; expanding markets, particularly through carbon trading; greenwashing.

Using time to make two key points. South African government policy is contradictory, and what links it all together is commitment to green capitalism. Government’s recent white paper which pretends to be a green paper. It is based on expanding markets and commodification. We know about this in South Africa because of the history of commodification of water.

Pablo Solon, former Bolivian ambassador to the United Nations, spoke next. He began be talking about the distinction between living for more and living better. Bolivian environmentalists have emphasized the latter, because natural resources are limited. This is why we helped create the Declaration of the Rights of Earth. We have been treating the Earth as if it has no rights, the way we used to treat slaves. Today there is an apartheid against Nature. Need to reject the approach towards the commodification of nature that characterizes contemporary global elites.

Answering some of the questions raised during the teach-in last night, Solon emphasized the absolute need to take power in order to reverse the trend towards commodification of the environment.

This session of the conference ended with a series of heartfelt questions from members of the audience about how climate change is going to effect their health and their livelihoods as rural people.

While putting together this report, I came across a couple of interesting sites:

Bleak, but not unexpected, news today. According to a new report published in Nature, sea level rise over the last two decades has taken place at a significantly faster rate than previously reported. To be specific, the acceleration is 25% higher than so far assumed. Coasts from Florida to Bangladesh are threatened.

Bleak, but not unexpected, news today. According to a new report published in Nature, sea level rise over the last two decades has taken place at a significantly faster rate than previously reported. To be specific, the acceleration is 25% higher than so far assumed. Coasts from Florida to Bangladesh are threatened.

The first film, Fever , explains the essential points of climate change and why it is so important to Indigenous Peoples.

The first film, Fever , explains the essential points of climate change and why it is so important to Indigenous Peoples.  The second film, Impacts, shows how large-scale industrial projects like plantations, coal mining and oil extraction impact indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and rights as well as contribute to global climate change.

The second film, Impacts, shows how large-scale industrial projects like plantations, coal mining and oil extraction impact indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and rights as well as contribute to global climate change.  The third film, Organization, provides examples of organizational tools and strategies used by indigenous peoples to protect their cultures, territories and rights.

The third film, Organization, provides examples of organizational tools and strategies used by indigenous peoples to protect their cultures, territories and rights.  The fourth and final film, Resilience, examines indigenous peoples’ increasing resilience to climate change by strengthening their customary systems and developing new approaches for adaptation.

The fourth and final film, Resilience, examines indigenous peoples’ increasing resilience to climate change by strengthening their customary systems and developing new approaches for adaptation.