The legislature in Arizona recently passed House Bill 2281. This document bans ethnic studies courses which promote race consciousness from public schools. This law of course comes on the heels of the draconian new immigration law SB 1070. It’s worth thinking about the relation between these two laws.

Education bill 2281 specifically prohibits a school district or charter school from including in its program of instruction  any courses or classes that: a) promote the overthrow of the United States government; b) promote resentment toward a race or class of people; c) are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group; d) advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.

any courses or classes that: a) promote the overthrow of the United States government; b) promote resentment toward a race or class of people; c) are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group; d) advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.

The ideology here of course is complete objectivity in the classroom. Supporters of this legislator are marching in lockstep with Daniel Horowitz, whose campaigns with Students for Academic Freedom have long blasted any form of politicization. As my colleague Malini Johar Schueller and I have argued in Dangerous Professors, this spurious notion of objectivity obscures the inherent politicization of dominant established curricula and attempts to roll back the (relatively slight) gains made by post-1960s social movements.

In fact, the explicit target of the legislation is the Mexican American Studies Department of the Tucson Unified School District. According to the department’s website, the education curriculum is designed to a) advocate for and provide curriculum that is centered within the pursuit of social justice; b) advocate for and provide curriculum that is centered within the Mexican American/Chicano cultural and historical experience.

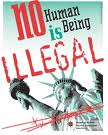

House Bill 2281 is a transparent attempt to clamp down on forces of ideological opposition within Arizona, a necessary  counterpart to SB 1070. Their symbiotic nature is made particularly evident when the bills are compared to similar bans enacted elsewhere.

counterpart to SB 1070. Their symbiotic nature is made particularly evident when the bills are compared to similar bans enacted elsewhere.

During the apartheid era in South Africa, for example, the ruling regime sought to silence critics of the status quo by banning them. Coupled with lynching, torture, and summary execution, the practice of banning was a key instrument of apartheid-era policy.

The banning of organizations or individuals was originally authorized in South Africa by the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950, and subsequently by the Internal Security Act of 1982. The definition of communism in these laws was extremely broad, including any activity allegedly promoting civil disturbances or disorder, promoting industrial, social, political, or economic change in the country, and encouraging hostility between whites and nonwhites so as to promote change or revolution. The main organizations banned under these laws were the Communist Party of South Africa, the African National Congress, and the Pan-African Congress.

More than 2,000 people were banned in South Africa from 1950 to 1990. Once a person was labeled a threat to security and public order, s/he essentially became a public nonentity. S/he would be confined to her or his home, would not be  allowed to meet with more than one person at a time (other than family members), to hold any offices in any organization, to speak publicly or to write for any publication. Banned persons were also barred from entering particular areas, buildings, and institutions, including law courts, schools, and newspaper offices.

allowed to meet with more than one person at a time (other than family members), to hold any offices in any organization, to speak publicly or to write for any publication. Banned persons were also barred from entering particular areas, buildings, and institutions, including law courts, schools, and newspaper offices.

The banning of ethnic studies departments in Arizona is an integral part of the reactionary program being advanced by the Right in the state. As the South African parallel suggests, the silencing of dissenting voices is just as essential to authoritarian hegemony as more obviously repressive forms of state power such as ethnic profiling in policing.

This assault on civil liberties and educational democracy needs to be taken just as seriously – and challenged just as ardently – as the state’s oppressive immigration legislation has been.