The largest grassroots environmental protest in decades came to a triumphant conclusion over the Labor Day weekend. In the course of two weeks, 1,252 people were arrested for sitting in peacefully in front of the White House in a bid to convince Barack Obama to reject the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline, which is slated to bring heavy oil from the tar sands deposits in Canada’s Alberta Province all the way across the U.S. to the Gulf Coast for refining. Organizers of the Tar Sands Action declared from the outset that this would be a litmus test for President Obama: he alone will make the decision whether to proceed with the Keystone project, and, as a result, his stance on this pivotal environmental issue will be a clear indication of his broader outlook on environmental affairs. At stake, in other words, is the support of the environmental movement for his reelection bid. The battle against extraction of oil from the tar sands is, however, about far more than simply throwing down the gauntlet to Obama’s Rightward-lurching presidency.

The largest grassroots environmental protest in decades came to a triumphant conclusion over the Labor Day weekend. In the course of two weeks, 1,252 people were arrested for sitting in peacefully in front of the White House in a bid to convince Barack Obama to reject the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline, which is slated to bring heavy oil from the tar sands deposits in Canada’s Alberta Province all the way across the U.S. to the Gulf Coast for refining. Organizers of the Tar Sands Action declared from the outset that this would be a litmus test for President Obama: he alone will make the decision whether to proceed with the Keystone project, and, as a result, his stance on this pivotal environmental issue will be a clear indication of his broader outlook on environmental affairs. At stake, in other words, is the support of the environmental movement for his reelection bid. The battle against extraction of oil from the tar sands is, however, about far more than simply throwing down the gauntlet to Obama’s Rightward-lurching presidency.

The struggle to stop the Keystone XL Pipeline is indicative of a key shift in the stakes and terms of contemporary environmental conflict, for the tar sands are but one instance of a far broader trend towards extreme extraction today. While the world is not about to run out of hydrocarbon energy sources, discoveries of new energy supplies such as oil fields have become increasingly infrequent and small in recent years. Such scarcity has been one of the key factors driving energy prices higher. As the quality and quantity of conventional sources of fossil fuel have diminished, the energy industry has turned to increasingly inaccessible sources in often hostile and fragile environments. The technology required to extract oil, gas, and coal reserves from such inaccessible sources has grown ever more complex, expensive, and environmentally destructive. The increasing scarcity of easily exploitable energy reserves, in other words, explains the rise of extreme extractive industries such hydrofracturing, deep sea oil drilling, mountaintop coal removal, and tar sands oil extraction. These new modes of extreme extraction are bringing forms of environmental destruction heretofore confined to the global South home to populations in the North who have for decades been relatively sheltered from the most aggressive efforts of the energy industry. Extreme extraction also significantly augments the release of greenhouse gases, intensifying climate change. For this reason, extreme extraction tends to go hand-in-hand with extreme weather and (un)natural disasters.

Yet if extreme extraction brings the environmental chickens home to roost, it also galvanizes new transnational forms of  solidarity. As the protests against the Keystone XL Pipeline over the last two weeks demonstrated, extreme extraction is forging coalitions that cross ethnic, regional, and national borders. In tandem with catalyzing such new links, the struggle against extreme extraction is also provoking the American environmental movement to adopt increasingly militant modes of direct action – forms of struggle often pioneered by environmental activists in the global South faced with the destruction of the natural world upon which their lives depend.

solidarity. As the protests against the Keystone XL Pipeline over the last two weeks demonstrated, extreme extraction is forging coalitions that cross ethnic, regional, and national borders. In tandem with catalyzing such new links, the struggle against extreme extraction is also provoking the American environmental movement to adopt increasingly militant modes of direct action – forms of struggle often pioneered by environmental activists in the global South faced with the destruction of the natural world upon which their lives depend.

* * *

Extreme extraction would seem to be an unlikely candidate for public support, particularly after the public relations debacle of last year’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. But neither the deep pockets nor the cynicism of the fossil fuel lobby should be underestimated. Oil from the Canadian tar sands, for example, is being marketed to the U.S. public using an incredibly duplicitous discourse of human rights that is shot through with thinly veiled forms of nationalism and racism. As a recent Ethical Oil campaign video demonstrates, tar sands oil is represented in this marketing campaign as a politically correct alternative to oil from oppressive regimes such as Saudi Arabia. “Unlike Conflict Oil from some of the world’s most politically oppressive and environmentally reckless regimes,” the Ethical Oil website states, “Ethical Oil is the “Fair Trade” choice in oil.” Never mind the fact that the U.S. has supported the Saudi regime for decades; oil from the Canadian tar sands is painted as a consumer choice in favor of democracy and human rights, akin to the decision to buy fair trade coffee.

Key to the Ethical Oil campaign is a contemporary version of the longstanding colonial trope of saving brown women from oppressive brown men. The Ethical Oil promotion video therefore focuses on the fact that “we” bankroll a state that “doesn’t allow women to drive, doesn’t allow them to leave their homes or work without their male guardian’s permission.” Instead of legitimating the rule of the British Raj or, in a more recent example of the circulation of this trope, the invasion of Iraq, this discourse of women’s rights is deployed by the Ethical Oil campaign to suggest that American consumers should support oil extracted in more democratic nations. As the Ethical Oil website has it, “Countries that produce Ethical Oil protect the rights of women, workers, indigenous peoples and other minorities including gays and lesbians. Conflict Oil regimes, by contrast, oppress their citizens and operate in secret with no accountability to voters, the press or independent judiciaries. Some Conflict Oil regimes even support terrorism.” The notion of “conflict” oil is intended to evoke the campaign against Blood Diamonds, suggesting that consumers who support the extraction and consumption of oil from Canada’s tar sands rather than from Saudi Arabia are striking a decisive blow for human rights.

Key to the Ethical Oil campaign is a contemporary version of the longstanding colonial trope of saving brown women from oppressive brown men. The Ethical Oil promotion video therefore focuses on the fact that “we” bankroll a state that “doesn’t allow women to drive, doesn’t allow them to leave their homes or work without their male guardian’s permission.” Instead of legitimating the rule of the British Raj or, in a more recent example of the circulation of this trope, the invasion of Iraq, this discourse of women’s rights is deployed by the Ethical Oil campaign to suggest that American consumers should support oil extracted in more democratic nations. As the Ethical Oil website has it, “Countries that produce Ethical Oil protect the rights of women, workers, indigenous peoples and other minorities including gays and lesbians. Conflict Oil regimes, by contrast, oppress their citizens and operate in secret with no accountability to voters, the press or independent judiciaries. Some Conflict Oil regimes even support terrorism.” The notion of “conflict” oil is intended to evoke the campaign against Blood Diamonds, suggesting that consumers who support the extraction and consumption of oil from Canada’s tar sands rather than from Saudi Arabia are striking a decisive blow for human rights.

Two huge fallacies underlie this apparently neat distinction between Ethical Oil and Conflict Oil. The first is the assumption that the world has to consume more oil, and that Americans must perforce choose between different sources of petroleum. Against this assumption, we should remember the admonitions of climate scientists such as James Hansen that we need to decarbonize the industrialized economies of the world with all possible dispatch if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change. Few serious analysts believe such a shift is going to be easy or even possible without transforming our current, growth-dependent capitalist system, but it is nonetheless clearly imperative for our collective survival that we make this change. This is a truth that the notion of ethical oil consumption, like other forms of consumer-oriented green capitalism, conveniently ignores.

The second whopping lie in the Ethical Oil campaign is the notion that any oil can ever be extracted in a wholly ethical  manner. Oil is a toxic substance whose extraction and consumption over the last century has significantly raised living standards in some parts of the world, but has also been inextricably tied to colonialism, imperialism, and other violations of people’s rights to self-determination, leading to widespread human rights abuses and the wholesale destruction of the environment. Furthermore, to continue to consume oil is to magnify the baleful impact of climate chaos around the world today and to ensure a bleak and increasingly violent world for future generations.

manner. Oil is a toxic substance whose extraction and consumption over the last century has significantly raised living standards in some parts of the world, but has also been inextricably tied to colonialism, imperialism, and other violations of people’s rights to self-determination, leading to widespread human rights abuses and the wholesale destruction of the environment. Furthermore, to continue to consume oil is to magnify the baleful impact of climate chaos around the world today and to ensure a bleak and increasingly violent world for future generations.

Oil from the tar sands, which the Ethical Oil campaign is of course designed to legitimate, is a perfect example of the violence of the energy industry. Tar sands oil is based on modes of extreme extraction that wreak unparalleled destruction on the environment and its denizens. Much of that destruction has been relatively invisible, however, since it takes place in the geographically isolated wilds of northern Alberta Province in Canada. An additional factor that makes extraction from the tar sands difficult for the general public to understand and to mobilize against is what Rob Nixon, in his recent book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, calls the “temporal dispersion” of environmental calamities. Like the acidification of the oceans, the thawing of the cryosphere, and many other aspects of climate change, the impact of oil and gas extraction from the Canadian tar sands does not fit within the spectacular visual frame that drives mainstream news media. As Nixon argues, the slow violence that characterizes many environmental catastrophes not only tends to make such disasters relatively invisible to much of the public, but also allows the corporations that perpetrate ecocide to wash their hands of the damage they cause since this violence often unfolds over decades rather than in the spectacular moment. The problem of slow violence is, as Nixon points out, at its heart a challenge of representation. This makes a politics of witnessing – using media that can reverse the geographical and temporal invisibility of environmental crimes – a particularly key mode of contemporary activism.

Melina Laboucan-Massimo’s Oil on Lubicon Land: A Photo Essay offers a powerful instance of such witnessing. Through a collage of photographs and a voice-over narrative, Laboucan-Massimo depicts the impact of three decades of oil and gas extraction on the territory of her people, the Lubicon-Cree First Nation. Lubicon land is now pockmarked by more than 2,600 oil and gas wells, and seventy percent of the tribe’s territory is leased for future “development.” Laboucan-Massimo stresses that this oil and gas extraction has taken place without consent of the Lubicon, infringing the provisions of the Canadian Constitution that protect aboriginal treaty rights. In addition, none of the estimated $14 billion worth of resources removed from Lubicon territory over the years have benefited the tribe materially. Instead, as Laboucan-Massimo demonstrates in her arresting photomontage, the beautiful boreal forests and peatlands that used to support a self-sufficient indigenous way of life based on hunting and gathering have been replaced by a blasted, pitted, and polluted industrial landscape. As indigenous activist Gitz Crazyboy put it during the Keystone protests, this effectively represents a fresh wave of genocide against First Nations people. To destroy the land that sustains indigenous people is also to destroy their culture, to make them dependent wards of an increasingly parsimonious state that has sanctioned the illegal exploitation of their lands.

Oil on Lubicon Land also makes the impact of extreme extraction visible by narrating the April 29, 2011 rupture in the Rainbow pipeline. This spill, one of many almost totally unreported pipeline ruptures over the last year in North America, released 4.5 million liters of toxic crude onto Lubicon land. If members of the tribe were already suffering from the slow violence of respiratory illnesses and cancer clusters produced by the oil and gas industry’s exploits on their land in recent decades, the oil spill rendered the toxicity of extreme extraction graphically visible. According to Laboucan-Massimo, the government not only failed to send out crews to deal with the spill but also did not notify affected communities of the dangers of the spill for almost a week. In a replay of the mendacious collaboration between government regulators and Big Oil that characterized the Deepwater Horizon spill, provincial authorities subsequently claimed that the peatland which absorbed much of the spill was an inert and isolated bog rather than a living ecosystem with vital connections to other parts of Lubicon land, including the aquifers that supply the Lubicon with drinking water.

Oil on Lubicon Land is not just a call for solidarity with the geographically isolated and politically marginalized Lubicon-Cree people, as important as such a call is. Melina Laboucan-Massimo’s photo essay has direct implications for the Keystone XL Pipeline, which will traverse the massive Ogallala aquifer – the source of 30% of America’s irrigation water and 82% of the drinking water for residents of the Plains states. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency gave the State Department’s Environmental Impact Statement on the Keystone XL a failing grade for reasons tied to the threat represented by the pipeline project to the Ogallala aquifer. The EPA noted, for instance, that the Environmental Impact Statement failed to adequately consider alternate routes for the pipeline that do not run through the Ogallala aquifer, and also failed to disclose or analyze the potential diluents that would have to be used to reduce the viscosity of the bitumen carried in the pipeline, information that would be essential to dealing with potential leaks. Such leaks are a very real concern given the fact that the existing Keystone pipeline ruptured in May 2011, releasing 20,000 gallons of crude in North Dakota. This was only one of the twelve spills that have plagued the Keystone over the last year. TransCanada Corporation’s successor pipeline, the Keystone XL, is, as its cute suffix suggests, designed to carry far more crude – double the quantity, in fact – far further, increasing the potential destructive impact of a rupture.

Oil on Lubicon Land is not just a call for solidarity with the geographically isolated and politically marginalized Lubicon-Cree people, as important as such a call is. Melina Laboucan-Massimo’s photo essay has direct implications for the Keystone XL Pipeline, which will traverse the massive Ogallala aquifer – the source of 30% of America’s irrigation water and 82% of the drinking water for residents of the Plains states. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency gave the State Department’s Environmental Impact Statement on the Keystone XL a failing grade for reasons tied to the threat represented by the pipeline project to the Ogallala aquifer. The EPA noted, for instance, that the Environmental Impact Statement failed to adequately consider alternate routes for the pipeline that do not run through the Ogallala aquifer, and also failed to disclose or analyze the potential diluents that would have to be used to reduce the viscosity of the bitumen carried in the pipeline, information that would be essential to dealing with potential leaks. Such leaks are a very real concern given the fact that the existing Keystone pipeline ruptured in May 2011, releasing 20,000 gallons of crude in North Dakota. This was only one of the twelve spills that have plagued the Keystone over the last year. TransCanada Corporation’s successor pipeline, the Keystone XL, is, as its cute suffix suggests, designed to carry far more crude – double the quantity, in fact – far further, increasing the potential destructive impact of a rupture.

Adding to these relatively immediate concerns about the pipeline’s potential damage to key water supplies, the EPA  report discusses the Environmental Impact Statement’s failure to assess the heightened greenhouse gas emissions associated with the project adequately. Exploitation of the Canadian tar sands is an incredibly energy-intensive process. The first step is to cut down huge swaths of boreal forest, a step that of course generates large amounts of carbon. Next, three-story high motorized shovels and dump trucks have to remove tons and tons of rock and soil to expose the underlying tar sands. Then, the dense bitumen that will be turned into synthetic crude has to be separated from the sand and clay with which it is surrounded. This can be done either by hauling the tar sands to processing plants, where natural gas and a gasoline-like product called naphtha are used to separate and process the bitumen, or by pumping steam underground to “cook” the bitumen over a two-week period, and then pumping the liquefied bitumen out of the ground. Either way, the amount of water and energy needed to extract the bitumen are extremely high, and the entire process creates massive amounts of greenhouse gases. Indeed, according to Naomi Klein, Canada’s carbon emissions are up 30% as a result of increasing exploitation of the tar sands, meaning that all other steps to be good environmental stewards taken by Canadians are meaningless.

report discusses the Environmental Impact Statement’s failure to assess the heightened greenhouse gas emissions associated with the project adequately. Exploitation of the Canadian tar sands is an incredibly energy-intensive process. The first step is to cut down huge swaths of boreal forest, a step that of course generates large amounts of carbon. Next, three-story high motorized shovels and dump trucks have to remove tons and tons of rock and soil to expose the underlying tar sands. Then, the dense bitumen that will be turned into synthetic crude has to be separated from the sand and clay with which it is surrounded. This can be done either by hauling the tar sands to processing plants, where natural gas and a gasoline-like product called naphtha are used to separate and process the bitumen, or by pumping steam underground to “cook” the bitumen over a two-week period, and then pumping the liquefied bitumen out of the ground. Either way, the amount of water and energy needed to extract the bitumen are extremely high, and the entire process creates massive amounts of greenhouse gases. Indeed, according to Naomi Klein, Canada’s carbon emissions are up 30% as a result of increasing exploitation of the tar sands, meaning that all other steps to be good environmental stewards taken by Canadians are meaningless.

The tar sands contain massive fossil fuel deposits. In fact, Canada increased its oil reserves by 3,600% when it decided to report its bitumen as economically recoverable “proven reserves” of petroleum in 2003, making it the possessor of the world’s second-largest oil supply. Nonetheless, in his book Powerdown: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World, Richard Heinberg predicted that, despite their abundance, the tar sands would not become a meaningful source of energy for the U.S. because the extraction process relies so heavily on cheap and abundant natural gas. What has changed since Heinberg published this prediction in 2004? In 2005, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act after an intense lobbying campaign from the extractive industry and from Vice President Dick Cheney’s Energy Task Force. As Josh Fox details in his film Gasland, the Energy Policy Act contained what’s known proverbially as the Halliburton Loophole to the Safe Drinking Water Act, a provision that authorizes corporations engaged in oil and gas exploration and extraction to inject known hazardous materials into land directly adjacent to underground drinking water supplies. The Halliburton Loophole also exempts such corporations from the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, and Superfund Law.

These legal changes were necessary because the recovery of natural gas has been vastly expanded using a technique known as hydraulic fracturing, or, more popularly, fracking. Like exploitation of the tar sands and other forms of extreme extraction, fracking is necessary because our nation’s unexploited large natural gas reserves are embedded in dense rock formations. To extract these relatively inaccessible reserves, energy companies inject a cocktail of water and secret proprietary fracturing fluids deep underground, where the toxic brew literally explodes, fracturing the rock formations and allowing the natural gas to be siphoned up to the surface. Significant amounts of the fracking fluids remain in the ground after the gas has been extracted. Despite releasing a report in 2004 (under heavy pressure from the Bush administration) that concluded that fracking “poses little or no threat to underground sources of drinking water,” in a 2010 study the EPA discovered toxins such as arsenic, copper, vanadium, and adamantanes in drinking water adjacent to drilling operations; these contaminants have been linked to illnesses such as cancer, kidney failure, anaemia, and fertility problems. The Natural Gas Subcommittee of the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board is currently studying ways to make hydraulic fracturing safer, but, as a letter from scientists at 22 leading universities states, six of the seven members of this subcommittee have current financial ties to the natural gas and oil industry. The public has good reason to be skeptical about the reports from such biased sources.

Immediately after passage of the Energy Policy Act in 2005, a bevvy of major energy corporations began the largest and most extensive domestic drilling campaign in history. They were building on drilling conducted since the Bureau of Land Management opened its extensive territories to drilling under pressure from Vice President Cheney in 2001, a move that resulted in the drilling of 450,000 wells in largely rural areas of the American west and south. The large quantities of natural gas recovered in the course of these earlier operations were key to making exploitation of the Canadian tar sands economically viable. Abundant and consequently relatively cheap sources of one fossil fuel hence facilitated extraction of another, with little thought given to the ultimate environmental and human toll of such energy intensive and polluting processes. As we have seen, however, both sources require extreme extraction techniques, both rely on dubious scientific claims about the safety of such techniques, and they each result in grievous environmental damage, both immediate and long-term.

Immediately after passage of the Energy Policy Act in 2005, a bevvy of major energy corporations began the largest and most extensive domestic drilling campaign in history. They were building on drilling conducted since the Bureau of Land Management opened its extensive territories to drilling under pressure from Vice President Cheney in 2001, a move that resulted in the drilling of 450,000 wells in largely rural areas of the American west and south. The large quantities of natural gas recovered in the course of these earlier operations were key to making exploitation of the Canadian tar sands economically viable. Abundant and consequently relatively cheap sources of one fossil fuel hence facilitated extraction of another, with little thought given to the ultimate environmental and human toll of such energy intensive and polluting processes. As we have seen, however, both sources require extreme extraction techniques, both rely on dubious scientific claims about the safety of such techniques, and they each result in grievous environmental damage, both immediate and long-term.

After 2005, drilling operations for natural gas using fracking were extended into the more highly populated areas of North America. In July 2008, Pennsylvania lifted a five-year moratorium on new drilling in state lands to allow access to the Marcellus shale, a sedimentary rock formation that extends under a large part of the Appalachian Basin, from New York’s finger lakes region, through central Pennsylvania, to West Virginia and Maryland. New York quickly streamlined its own leasing process to catch up with Pennsylvania, despite the lack of any significant objective assessments of the environmental and health impacts of fracking. A recent New York Times article revealed that a yet-to-be-released report into the impact of fracking in New York state was conducted by Ecology and Environment, Inc., a consulting firm that “counts oil and gas companies among its clients and that could gain business from increased drilling in the state.” Despite widespread public concern about the paucity and dubious objectivity of environmental impact assessments, New York State officials report they expect to receive applications to drill up to 2,500 horizontal and vertical wells on the Marcellus Shale during a peak year — and about 1,600 in an average year — over a 30-year period. That’s 48,000 wells in New York State alone. Many of these wells will be in areas near the pristine watersheds that feed the renowned public water supply of New York City.

Extreme extraction has arrived on the doorstep of the world’s most affluent and powerful city. Like exploitation of the tar sands, fracking may imperil the water supply of millions of people. The environmental chickens have really come home to roost. This threat is transforming the U.S. environmental movement. For the Indian ecologist Ramachandra Guha, author of How Much Should a Person Consume and many other important works of environmental history, the environmental movement in the U.S. has tended to focus on preservation of what is represented as pristine natural wilderness. Guha argues, in contrast, that environmental protest in India and other zones of the global South has focused more on protests against the encroachment on communal natural resources by what he calls the urban-industrial complex. Since these environmental conflicts hinge on control over resources key to community survival, they tend to center on issues of human rights and distributive justice. Such struggles also tend to generate relatively radical forms of protest such as direct action since they have to do with what Gitz Crazyboy called “taking back our futures.” Guha’s opposition breaks down when it comes to the Environmental Justice Movement in the U.S., which has fought the disproportionate location of polluting industries and toxic dumps in communities of color for at least three decades. Nonetheless, Guha’s analysis is an accurate characterization of the single-issue orientation of most mainstream American environmental organizations.

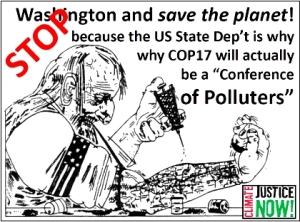

The campaign against the Keystone XL Pipeline that unfolded over the last two weeks suggests, though, that Guha’s critical characterization of the U.S. environmental movement needs to be revised. As extreme extraction becomes increasingly prevalent and increasingly threatening in the U.S., the American environmental movement is likely to converge with environmental activism in the global South around issues of social justice and collective survival. During the Keystone XL protest in front of the White House, for example, the tar sands were represented as a carbon bomb that needs to be defused. This image of a ticking bomb captures both the ominous long-term temporal menace represented by climate change as well as the danger of immediate destruction that characterizes an exploding pipeline – and, I would add, the volatile process of hydraulic fracturing. Notably, the Tar Sands Action also involved the formation of coalitions and solidarity between groups such as the Indigenous Environmental Network, rural farmers’ organizations, protesters from the Gulf Coast, and urban activists from the Northeast. And finally, the Tar Sands Action took the form of the largest environmental nonviolent direct action protest in several generations. None of these momentous changes in the environmental movement came automatically or easily; it took a lot of work by organizers to bring this protest to fruition. A lot more work remains to be done to adequately include and highlight the concerns of underrepresented groups such as environmental justice activists in the emerging movement for climate justice. Nonetheless, the Tar Sands Action represents an important milestone in the fight to take back our future.

This article was initially posted on Counterpunch.

Photocredits, in order of appearance: Josh Lopez, Milan Ilnyckyj, Shadia Fayne Wood, Shadia Fayne Wood, Shadia Fayne Wood, Josh Lopez, Josh Lopez.

The first film, Fever , explains the essential points of climate change and why it is so important to Indigenous Peoples.

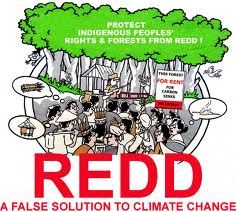

The first film, Fever , explains the essential points of climate change and why it is so important to Indigenous Peoples.  The second film, Impacts, shows how large-scale industrial projects like plantations, coal mining and oil extraction impact indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and rights as well as contribute to global climate change.

The second film, Impacts, shows how large-scale industrial projects like plantations, coal mining and oil extraction impact indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and rights as well as contribute to global climate change.  The third film, Organization, provides examples of organizational tools and strategies used by indigenous peoples to protect their cultures, territories and rights.

The third film, Organization, provides examples of organizational tools and strategies used by indigenous peoples to protect their cultures, territories and rights.  The fourth and final film, Resilience, examines indigenous peoples’ increasing resilience to climate change by strengthening their customary systems and developing new approaches for adaptation.

The fourth and final film, Resilience, examines indigenous peoples’ increasing resilience to climate change by strengthening their customary systems and developing new approaches for adaptation.