This is the final session in a two-day workshop organized by the Transnational Institute, a group that bills itself as “a worldwide fellowship of scholar activists.” The overarching theme of the workshop was Defying Dystopia: Struggle Against Climate Change, Security States, and Disaster Industries.

This is the final session in a two-day workshop organized by the Transnational Institute, a group that bills itself as “a worldwide fellowship of scholar activists.” The overarching theme of the workshop was Defying Dystopia: Struggle Against Climate Change, Security States, and Disaster Industries.

Hilary Wainwright, “Climate Justice, Climate Capitalism, and Social Movements”

This paper is inspired by the work of Ruth First, an exemplary scholar-activist and committed journalist.

All the social movements are challenging the logic of capital today, but there’s something specific about labor in that confrontation. This paper explores the emergence of networks of solidarity between labor and environmental activists, focusing in particular on the million climate jobs campaign. What I and Jacky are interested in exploring is the associative power of labor. We’re interested in a reclaiming of the social after decades of neoliberal appropriation of the ideas of individualism that emerged from social movements of the 1960s and 1970s. We’re interested in reclaiming the social, including social individualism, to establish a notion of collectivity which isn’t the collective over and above the individual, but of networks of solidarity between people.

We’re thinking of a notion of labor in the broadest possible, feminist sense, understanding labor in terms of self-employment, domestic labor (outside the waged economy) and unemployed labor, which plays such a key role in the capitalist economy. We’re also thinking of free labor, such as that involved in the open software movement, and the labor involved in consumption.

The one million climate jobs campaign is a response to the convergence of climate change and unemployment, particularly in South Africa, where 3 million young people, 40% of the population, are unemployed. The aim of this campaign is to organize in the townships and to forge alliances between trade unions and environmental groups. And then there’s also the building of organization among self-employed groups such as the Waste Pickers. They’re interesting because they’re not organizing simply to improve the price of their labor, but organizing to gain control over the waste management systems in order to use their knowledge of waste to push for genuine recycling, such as compost. So they’re directly hitting at the logic of capital.

Traditional unions in high carbon industries are also beginning to think about how they can use their knowledge and power to convert their industries to more sustainable footing. I remember in the late 1970s, there were massive rationalizations of industries in the UK. Lucas Aerospace workers were top level designers of latest destructive technologies of the time; they realized that they didn’t want to just organize for better wages, but wanted to do something else that didn’t involve the military-industrial complex (many of them were involved in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament). They had sense that their skills could be producing totally different things, including environmental machines. They produced an alternative plan for their firm and for the UK, a model which had a significant influence on radical politics in that period.

Some contemporary industries need a planned decline – mining, for example. But some, such as the automotive industry, for example, have tremendous potential for transitioning to sustainable production. NUMSA (National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa), whom I met recently, has set up worker teams in each area that can be converted into new alternative industries.

In all these spheres, there’s a sense that the financial crisis and the crisis of neoliberalism has begun to have an impact on how labor is organizing. It’s important, in other words, not to think – oh hell, now there’s the climate crisis, what do we do? – but rather to think about what existing forms of organization we can use.

Admittedly, we have to recognize how difficult things are, how precarious all the positive things I’m pointing to are. There’s a trend towards autonomist politics that’s influencing the labor movement. Yesterday I was with an organizer of Streetnet, an international organization of street vendors that developed when street vendors were faced with being banned from public space during the run-up to the World Cup, and when municipal workers refused to “clean them up.”

In most countries, the labor movement abrogated politics to social democratic parties and saw themselves simply as fighting for narrow wage issues. But as the parties have given up on oppositional politics, trade unions have sometimes developed into vibrant political organizations. So this paper is about realistic things that can be done to stop climate change.

I’d like to try to systematize discussion of different sectors:

- One area, like mining, needs to be shut down

- Then there are others that need to be converted, like car manufacturing and waste processing

- Finally, there are unions moving into new green technologies

- new jobs, including in the public sector and the solidarity economy

NUMSA teams are working with communities to see what technologies are useful to people, and then using their bargaining power to push for production in these areas. This might be a way of occupying the claim of green capitalism.

The one million jobs campaign doesn’t just focus on jobs, but also on exposing the inequalities behind climate change and structural economic inequalities.

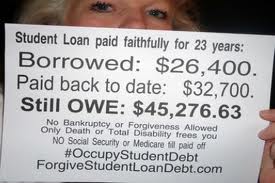

Throughout the whole neoliberal period, we’ve seen a weakening of democracy and a hollowing out of the legitimacy of the whole political system. This is one of the driving factors behind criminalization; democracy was a legitimizing process. That’s been  breaking down, and a gap opening up between the political class and the people. But the other side is the search for meaningful alternatives. That’s the significance of the Occupy movement, and why it won’t go away. It’s now clear that the political system is not worth entering.

breaking down, and a gap opening up between the political class and the people. But the other side is the search for meaningful alternatives. That’s the significance of the Occupy movement, and why it won’t go away. It’s now clear that the political system is not worth entering.

These political spaces are not formed yet. In developing a green economy, we’ve got to refine our understanding of capitalism. We need to understand the anti-market character of capitalism. The spaces created by the Occupy movement are growing. That’s why we’re going to see new convergences around new forms of political power.

Susan George, “People’s Security on a Protected Planet”

What are people already doing about military-industrial-security complex? I don’t really see what people can do outside what Hilary has just described happenign in the labor movement. That is, broadening alliances, making networks, etc. I see no hope other than these strategies in the face of the groups we’re confronted with, who are really deciding who is going to be allowed to live and who will be left to die.

Who is this book for and who is it against? We can’t use academic jargon or we’ll put people off immediately. But we’ve also got to be subtle and factual. Some of the papers given in this workshop would be accessible enough, but some aren’t.

I’m also troubled by our basic premise. Are we really going to say that there’s no hope left of reducing and stopping climate change. I don’t use this line with audiences. I say, yes, change your behavior. But don’t think that this is going to be enough to change the world. It’s not the right scale and scope, even if you can be an example. But we can’t give the impression that we’re giving up, that we’re going to the 4 degree, which will become the 9 degree, world. I’ve got four grandchildren and I’m just not really willing to go there.

We want to convey success stories – you could be part of something really big, the biggest social movement in history. But we don’t want to sugarcoat things since we need to convey the odds we’re up against.

So we want to talk about the major actors. One is clearly the military-industrial-security complex. Should we be happy when the Navy starts running jets on vegetable oil, should we be happy? No, clearly we shouldn’t. In a way, the European military are worse than the Pentagon in this context. We need to define these actors more systematically and explain their impacts. But also, what are the strengths and weaknesses in these actors? What are their Achilles heels?

Second actor: business, in a general way. The World Business Council for Sustainable Development is here. They invented corporate self-regulation in the area of sustainable development. The business lobbies are really eating away at individual security, particularly everywhere where there’s an austerity program. In this area, the neoliberals have won. In 2008, we might have thought that everyone would see how bankrupt the system was, but now they’ve won: they feel much freer to take us back to the 19th century. The Indignados and the Occupiers are great, but they’re not at the same level of command and control. If you have a chance, look at the FT issue of the 500 largest companies. The top 10 are all oil and banks, followed by mining, arms companies. Its the same in the UK, US, and China. It really is like the 19th century, which continues to spew out carbon.

Another ambiguity: finance. There’s a report from 260 odd corporations that manage other people’s funds which together control $15 trillion. They are saying to the US government that they want guidelines for investing in green technology and industry. But they don’t invest because they don’t get guidelines from the US. Should we support those people? I don’t want to give venture capitalists a longer lease on life, but I don’t want the planet to become Venus. What do we do?

Other actors: governments. Land grabs, geoengineering, competitivity, all this is government. Can we change these governments and make them take better positions?

The intergovernmental organizations, like the WTO, which continues to fuel fossil fuels, and supports patent laws.

The UN. Should we all go to Qatar to influence the next UN meeting? The IPCC – shouldn’t we have a closer relation with them? Couldn’t they benefit from learning about some of the topics we’ve discussed in this workshop?

The planet itself: the biological systems of the Earth. Nature is striking back. Despite the technophilia of other actors, Nature always wins. IF you try to fight biophysical systems, you lose. “Exceptional events” like storms, droughts, etc already killed 350,000 people last year, according to estimates. Everyone now agrees because of IPCC special report that the intensity of these phenomena are going to increase. Even earthquakes, we now know, are caused by climate change. So Nature is striking back.

Final actor: the people. Here we have the numbers, and we have the ideas. We’re developing the language to talk about these issues, we’re developing the language. If we want to develop alliances today, we need to keep in mind that knowledge and politics are interconnected.

We need to give the poor – who know what’s wrong with their lives – better knowledge of their enemies, the rich.

We also need to do more study of organizational techniques. Hilary has given good examples of what labor can do, but there are many cases in which labor does not consider women’s work, informal work, etc as part of their remit. There are lots of other allies: the environmental movements, the social movements, pensioners, etc. We have to work hard on who might be the potential allies and then go to talk to them. The peace movement, for example, doesn’t seem to be a part of this movement. That’s one big area of people who are good-hearted but don’t have the detailed knowledge that we do of these issues. We need to organize them into the kind of coalition that Johan Galtung has done.

My last point: let’s use democracy, or what we’ve got left of it, while we still can. We can still use freedom of information acts, for example, and we should.

Discussion:

We’re facing the question of two main paths in relation to labor: one is to provide more green services, the other is degrowth. The latter is very promising, but difficult for the unions to accept.

We’re seeing a rising movement that has more systemic analyses, but these movements – Arab Spring, Indignados – aren’t associated in the public mind with environmentalism. This is an issue we have to tackle.

What happened to the Climate Justice Movement? It was something cobbled together from a bit of the global justice movement, the peace movement, etc. But that seemed fine for Copenhagen because there was a huge crescendo of public expectation, with the notion that we wanted a fair and binding treaty. Once we began to get into the details, there was a fragmentation: would India and China just get to keep developing along capitalist lines? Elites get to maintain their hegemony simply by doing nothing, leaving us always responding to their agenda. The challenge we have is on alliances; how can we find common ground between labor movement and green capitalists.

The people’s movements in the global South and North are creating so many vibrant forms and are so filled with good ideas. We really need to include some of these positive developments so that the book that comes out of these workshops isn’t too depressing and negative.