Earlier this week I went to see a film in the MOMA New Directors/New Films series. The film was They’ll Come Back, a meditative, beautifully immersive film directed by the Brazilian Marcello Lordello. The film tells the story of a teenage girl from a wealthy family who is left by the side of a road in the middle of the countryside as a punishment for fighting with her brother. Her parents do not return – we learn later that they are both left in a coma after a car hits them – and the girl, whose name is Cris, is left by herself when her brother hikes off in search of a gas station.

Earlier this week I went to see a film in the MOMA New Directors/New Films series. The film was They’ll Come Back, a meditative, beautifully immersive film directed by the Brazilian Marcello Lordello. The film tells the story of a teenage girl from a wealthy family who is left by the side of a road in the middle of the countryside as a punishment for fighting with her brother. Her parents do not return – we learn later that they are both left in a coma after a car hits them – and the girl, whose name is Cris, is left by herself when her brother hikes off in search of a gas station.

They’ll Come Back follows Cris as she moves from one good Samaritan to the next. She initially is helped by a boy who takes her to stay with his mother and sister, who are squatters on land occupied by other landless families under the leadership of members of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement. The film shows Cris’s disorientation in the rural world inhabited by these people, and traces her gradual return home to the affluent but sterile, reactionary world of city-dwelling bourgeois family. Of course she returns home completely changed.

Lordello’s film offers a gentle critique of the massive inequalities of contemporary Brazilian society. The film’s conceit of following the unformed girl Cris reminded me in some ways of Hollywood’s anti-apartheid films of the 1980s. The assumption behind those films was always that white audiences couldn’t or wouldn’t identify with black actors, so each film had to have a middle class white protagonist, whose eyes are opened to the injustice of apartheid by an increasingly violent train of events. Similarly, They’ll Come Back clearly expects Brazilian audience members to identify with the middle class, extremely white character Cris as she journeys through the worlds of her poorer, darker-skinned compatriots. What sort of film, I wondered as I sat watching They’ll Come Back, would result if the lens were turned around and a kid from the rural regions of Brazil were suddenly catapulted into the antiseptic elite world into which Cris was born.

Lordello’s film offers a gentle critique of the massive inequalities of contemporary Brazilian society. The film’s conceit of following the unformed girl Cris reminded me in some ways of Hollywood’s anti-apartheid films of the 1980s. The assumption behind those films was always that white audiences couldn’t or wouldn’t identify with black actors, so each film had to have a middle class white protagonist, whose eyes are opened to the injustice of apartheid by an increasingly violent train of events. Similarly, They’ll Come Back clearly expects Brazilian audience members to identify with the middle class, extremely white character Cris as she journeys through the worlds of her poorer, darker-skinned compatriots. What sort of film, I wondered as I sat watching They’ll Come Back, would result if the lens were turned around and a kid from the rural regions of Brazil were suddenly catapulted into the antiseptic elite world into which Cris was born.

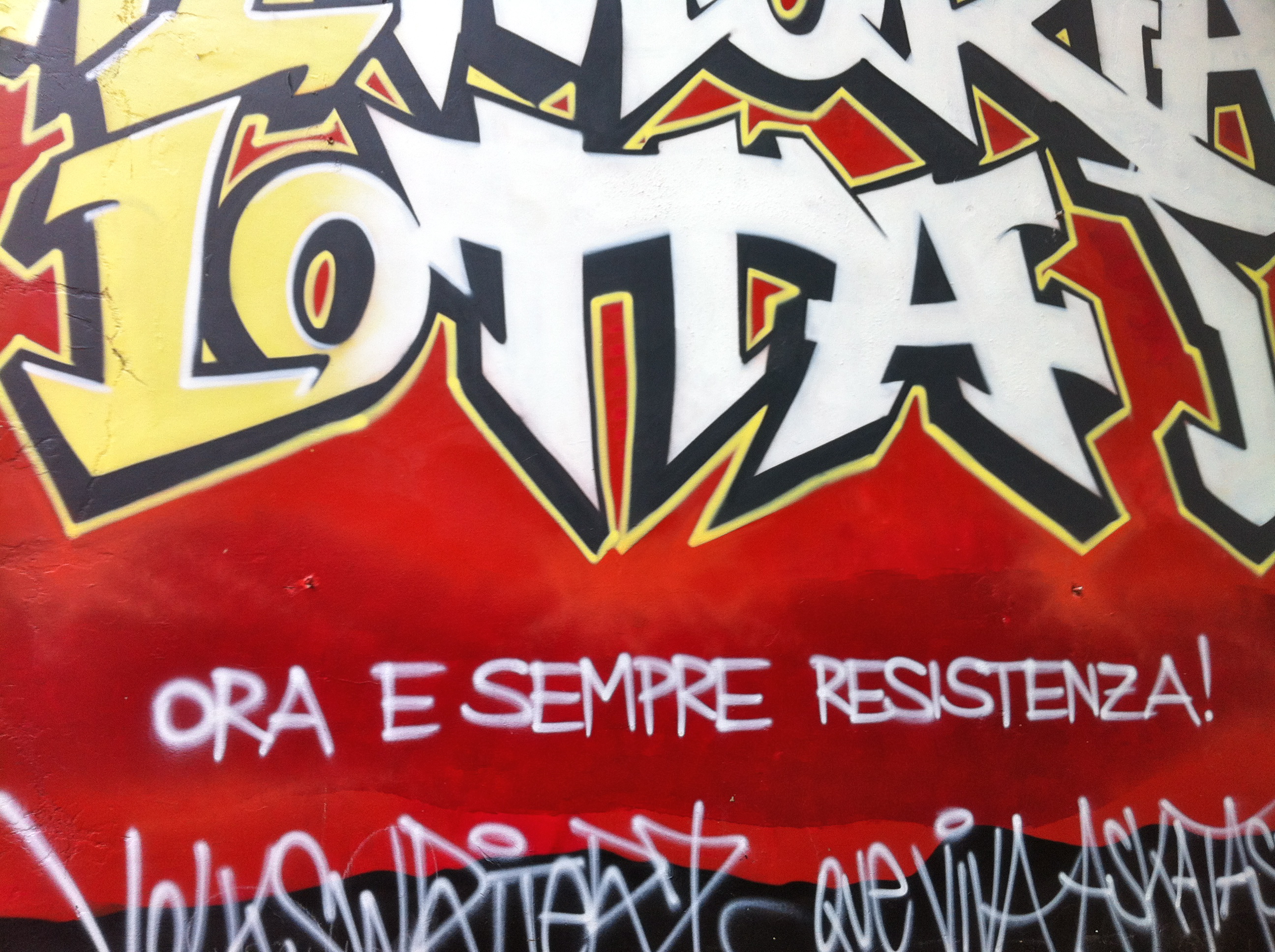

This thought set me wondering about representations of the landless. With exceptions such as the Courbet painting at the outset of this post, the Western landscape tradition has tended to represent rural areas as idyllic zones of repose and retreat from the hectic crowds of modern urban life. Sebastiao Salgado’s photograph above offers a far more challenging view of the militancy of landless workers that is clearly influence by the Brazilian context.

Given the forms of accumulation by dispossession that David Harvey analyzes as increasingly characteristic of contemporary capitalism, what kinds of representations of landless people do we find in the media today? They’ll Come Back offers a glancing one, at best. Here’s the film’s trailer; it starts at the end of the film and works back to the beginning. As this clip shows, the MST interlude is a brief one:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4IpJqdrY1S0]

A brief search turned up a couple of other films, both documentaries, depicting Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (whose acronym in Portuguese is MST).

History Did Not End is a documentary about the MST directed by the Italian Mario Alemi:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3gKYvCR52Y]

The NGO Other Worlds, which is also behind the Harvesting Justice project, has also done a documentary about MST:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8pCRs8e__0g]

In addition to such visual representations, there’s also the recent important book by Wendy Wolforth, This Land Is Ours Now, which discusses the rise and subsequent crisis of the MST.

We need more fictional or at least creative representations of such organizations. Such representations can offer us a sense of why such movements arise, what keeps them alive, and how they might be linked more effectively to one another.