Closed-door negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Trade Agreement = threats to environmental laws protecting the global commons.

Month: March 2013

Earlier this week, David Harvey appeared on a panel about contemporary Land Grabs along with activists Somnath Mukherjee, Smita Narula, Kathy LeMons Walker. I unfortunately was not able to attend. In searching fruitlessly for a video of the event, I nonetheless came across some interesting materials online.

Earlier this week, David Harvey appeared on a panel about contemporary Land Grabs along with activists Somnath Mukherjee, Smita Narula, Kathy LeMons Walker. I unfortunately was not able to attend. In searching fruitlessly for a video of the event, I nonetheless came across some interesting materials online.

The first is a video of a talk David Harvey did with Medha Patkar, founder of the anti-dam organization Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save the Narmada Campaign), and founder of the National Coalition of People’s Movements. This was a fascinating dialogue between a key activist working to roll back land grabs and an theorist who provides an incredibly important overview of capitalism’s strategies of accumulation by dispossession, of which land grabs are a key strategy. Here’s the video:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_Ia93DURSY]

I also came across a really interesting blog post by Raj Patel that analyzes a 2010 World Bank report on Land Grabs.

Last of all, I came across my own transcript of the discussion between Harvey and Patkar (I attended the event, which was held in an Occupy-aligned space near Wall Street). Here’s a link to my transcript.

From the perspective of a cultural critic, I want to ask what forms of hegemony need to be established in order for these sorts of land grabs to take place. Part of the problem may be that many of these activities remain invisible to most of the public in imperial nations such as the U.S. In this context, it might be worth recalling Fredric Jameson’s argument in Nationalism, Colonialism, and Literature that colonialism shifted a significant structural segment of the economic system overseas, beyond the metropolis, outside the quotidian experience of imperial subjects, rendering significant segments of everyday life unknown and unimaginable for these subjects.

But while Jameson’s point may make some sense in relation to land grabs, I think it’s important to see such strategies of accumulation by dispossession in a broader context, as part of an ensemble that includes free trade agreements, Structural Adjustment Policies, transnational flows of migrants, food riots, and uprisings such as the Arab Spring. So ultimately I think a position such as Edward Said’s in the same volume as Jameson makes more sense: to see the anxiety that permeates much modernist (and contemporary) cultural production as a product of the troubling of fixed borders that results from empire. It is probably also worth thinking about land grabs as part of a broader cultural of uneven development. Bret Benjamin’s Invested Interests is an important investigation of the culture of contemporary accumulation by dispossession. I’m sure there are other examples of cultural studies work along these lines. I’d love to hear suggestions…

Upcoming World Social Forum to be held in Tunisia, origin of the Arab Spring. The WSF promises to be an important convergence of global justice organizations.

New corporate land grabs in West Africa sponsored by the G8

The European tradition of landscape painting  created idealized representations of an arcadian world populated by shepherds and nymphs. The evenly distributed planes of sloping land in paintings by artists such as Poussin (one of whose works is featured to the right) created a balanced sense of landscape that reflected an idealized social order. These ordered representations of the land were given form in the ornate geometrical

created idealized representations of an arcadian world populated by shepherds and nymphs. The evenly distributed planes of sloping land in paintings by artists such as Poussin (one of whose works is featured to the right) created a balanced sense of landscape that reflected an idealized social order. These ordered representations of the land were given form in the ornate geometrical  symmetries of Renaissance Italian and French gardens such as those of Versailles, and, later, in the carefully constructed simulacrum of nature found in the gardens of English country houses.

symmetries of Renaissance Italian and French gardens such as those of Versailles, and, later, in the carefully constructed simulacrum of nature found in the gardens of English country houses.

Ironically, Poussin and other landscape artists such as Claude Lorrain created their works shortly before the onset of capitalism broke apart the stable feudal order that tied workers to the land, setting off a series of enclosures that radically dispossessed peasant communities across Europe. Similarly, the apparent self-enclosed order of the English garden was often a product of the brutal landscapes of exploitation that characterized slavery-driven sugar plantations in the Caribbean.

Each age, it seems, creates images of the landscape that just as often obscure the underlying social relations that produce nature as they idealize those social relations and the configuration of land produced by them.

What representations of landscape is our epoch creating?

It should not be much of a surprise that some of the most interesting depictions of contemporary landscapes depict a land blasted by industrialization and extreme extraction of various sorts. Edward Burtynsky’s series on Oil is typical in this regard. Burtynsky traces the various stages in the life of oil, from extraction (featured at the right) to the auto plants, flyovers, and fast food joints of Detroit and Los Angeles, to the toxic shipbreaking yards of Bangladesh.

His work is important since oil is such a contradictory substance. It is the lifeblood of US late capitalist culture, and yet is remains thoroughly invisible to most Americans. They see neither its  sites of extraction or refinement, and seldom think about the ways in which oil fuels virtually every aspect of life in the US, often at a serious toll of resources and blood for people in other parts of the world.

sites of extraction or refinement, and seldom think about the ways in which oil fuels virtually every aspect of life in the US, often at a serious toll of resources and blood for people in other parts of the world.

Other artist-activists have produced work which seeks to make this environmental toll visible. The Nigerian photographer George Osodi, for example, documents the massive environmental and social destruction caused in the Niger delta region of his country in a series of photographs reproduced in a montage here:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzZCifz-XCA]

Nor are established forms of extraction such as petroleum the only form of manufacturing toxic industrial landscapes. The short photomontage Oil on Lubicon Land by Melina Laboucan-Massimo, a member of the Lubicon Cree First Nation and a Climate and Energy Campaigner with Greenpeace, describes the impact of oil and gas developments and the recent oil spill in the traditional territory of the Lubicon Cree in northern Alberta:

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qz3nSscXamI]

There are many other artists working today on Manufactured Landscapes. Indeed, this geographical awareness, and the critical, investigative spirit that animates such depictions, could be said to be one of the most important trends in contemporary artwork. A key institution in supporting such work is the Center of Land Use Interpretation, whose website features photomontages every bit as devastating as those I’ve featured in this post.

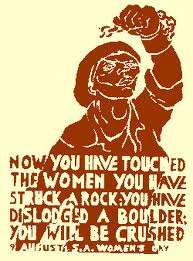

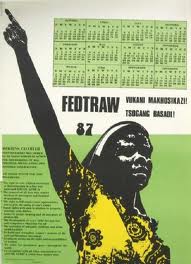

Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo’ – You Strike a Woman, You Strike a Rock. This slogan has come to define the struggle of women against oppression in South Africa. The rallying cry originates in a 1956 march led by women against the apartheid regime’s odious pass laws, which controlled the movement of people of color within the country.

Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo’ – You Strike a Woman, You Strike a Rock. This slogan has come to define the struggle of women against oppression in South Africa. The rallying cry originates in a 1956 march led by women against the apartheid regime’s odious pass laws, which controlled the movement of people of color within the country.

Despite the gains made in South Africa in the intervening years, women continue to face deep inequalities and oppression. The country has one of the highest rates of rape in the world, for example. For this reason, the tradition of women fighting back fearlessly against apartheid is an important one to remember during Women’s History Month.

Of course, South Africa is not the only country where women face enduring struggles against patriarchy. This weekend, women from around the world gathered here in New York at the United Nations for the 57th session of the UN Commission on Women. At a side event to the conference, a group of activists emerging from civil society networks that mobilized for last summer’s Rio+20 conference spoke out about the challenges posed to women around the world by unsustainable development.

Indigenous women from Guatemala talked, for example, about having to walk for 2-4 hours per day in order to retrieve water for domestic use since extractive mining operations in their communities are consuming the lion’s share of public water supplies. An activist from Colombia talked about the often-violent displacement of women by the “green grabbing” activities of large-scale agrofuel production companies. Linking violence against women’s bodies with structural economic forms of violence, a woman from Fiji underlined the necessity of thinking (and mobilizing) across different scales.

Indigenous women from Guatemala talked, for example, about having to walk for 2-4 hours per day in order to retrieve water for domestic use since extractive mining operations in their communities are consuming the lion’s share of public water supplies. An activist from Colombia talked about the often-violent displacement of women by the “green grabbing” activities of large-scale agrofuel production companies. Linking violence against women’s bodies with structural economic forms of violence, a woman from Fiji underlined the necessity of thinking (and mobilizing) across different scales.

An excellent report on the conference can be found here. And here’s a link to the Women’s Major Group, the organization founded following the Rio+20 conference to militate for a just and sustainable future.

In the Old Testament, the sea monster Leviathan offers an image of the staggering power of nature. Job proclaims that “any hope of subduing him is false; the mere sight of him is overpowering.” Leviathan “makes the depths churn like a boiling cauldron and stirs up the sea like a pot of ointment.”

In the Old Testament, the sea monster Leviathan offers an image of the staggering power of nature. Job proclaims that “any hope of subduing him is false; the mere sight of him is overpowering.” Leviathan “makes the depths churn like a boiling cauldron and stirs up the sea like a pot of ointment.”

Fittingly, the experimental documentary Leviathan begins with these references to our ancestors’ awed stance before the force of nature. The irony though is that Leviathan is no longer a sea monster who threatens humanity with his awesome power. Instead, we humans are become the monsters who threaten to extinguish all life in the briny depths.

Leviathan is set on a fishing trawler working off the coast of Massachusetts. The film challenges existing conventions of documentary by refusing conventional “voice of God” orienting narration, and instead plunging us into the tactile experience of life – and death – aboard the trawler with a visceral immediacy that is nearly overwhelming.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9uqyNKK3HYU]

Leviathan is produced by Lucien Castaign-Taylor and colleagues at Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab. The filmmakers used GoPro cameras favored by extreme sport enthusiasts in order to capture the savage toll on both the sea and fishermen exacted by contemporary commercial fishing. The film extends Walter Benjamin’s pioneering arguments about film as a surgical opening up of the guts of reality, allowing viewers to travel through sight and sound through the many horrifically violent aspects of life aboard the fishing trawler.

This is one of the most radical films I have seen, and surely offers a massive challenge to existing documentary conventions. Indeed, the film asks all those who seek to represent the world to rethink the ways in which they do so. How, the film intimates, can we capture lived experience with the immediacy which is its due. Given the increasing accessibility of multimedia means of reproduction and distribution, I think all creative workers seeking to document particular aspects of the world today should be asking what new forms of fidelity are possible.

In this aim, Leviathan is a huge inspiration. It offers a potent vindication for Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, whose goal is to provide “an academic and institutional context for the development of creative work and research that is itself constitutively visual or acoustic — conducted through audiovisual media rather than purely verbal sign systems — and which may thus complement the human sciences’ and humanities’ traditionally exclusive reliance on the written word.”

I think that the written word still has an important role to play, however. It’s very useful, for example, to juxtapose Leviathan‘s brutal corporeal account of the obliteration of life in the Atlantic with recent reports on the parlous state of the oceans. According to the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, the world’s oceans are facing a multifaceted degradation that threatens a mass extinction unlike anything we have ever seen. Multiple stress factors – including pollution, warming, acidification, overfishing and hypoxia – are driving a degeneration of the oceans that is occurring far faster than experts anticipated. If not curbed through serious changes in our collective behavior, the oceans will undergo an extinction event on the order of the greatest mass extinctions in the planet’s history.

When Leviathan rises up, the Bible tells us, the mighty are terrified, and retreat before his thrashing. If the sea monster was once a symbol of Nature’s awesome power, we live in times when we have appropriated the awesome power of nature. Yet if we extinguish live in the seas, we will ultimately kill ourselves. It is our current unsustainable capitalist system, which seeks infinite growth on a finite planet, that should truly be defined as the new leviathan. We should be filled with fear and trembling in the face of this monstrous power which we have created, and which now threatens to undo us.

I’m late on this one, but many of the suggested activities are still valid.

Big victory in the battle against fracking!

This post includes a petition to oppose Genetically Engineered eucalyptus plantations in the US. Join the MST in opposition!