Just came from an amazing event of the South African rural women’s movements. There were nominal speakers, but the real focus of the event were the groups of women who trooped in, dressed in traditional clothing, singing and dancing songs from the anti-apartheid struggle. After reading about and watching films of these struggles for so many years, it was really spine chilling to have these women standing right in front of me chanting. So much electric energy and passion. If only these women could get into the COP proceedings, they could totally shut it down.

Just came from an amazing event of the South African rural women’s movements. There were nominal speakers, but the real focus of the event were the groups of women who trooped in, dressed in traditional clothing, singing and dancing songs from the anti-apartheid struggle. After reading about and watching films of these struggles for so many years, it was really spine chilling to have these women standing right in front of me chanting. So much electric energy and passion. If only these women could get into the COP proceedings, they could totally shut it down.

After this, I went back up the hill to the University of Kwazulu-Natal where the People’s Space is located to hear a teach-in organized by Patrick Bond. As I walked in, Joel Kovel was talking about how capitalism began with enclosure of the commons and separation of the producers from the means of production. The Occupy Movement, Kovel argues, is an attempt to reassert the control over the collective means of production that were taken away from folks. Wall Street is so named because it was the site of one of the first capitalist enclosures in North America, and also of one of the first slave markets.

We should not fool ourselves into thinking that we can vote capitalism out of power. Our only hope is to create alternative or autonomous zones within the capitalist world, which, if extended far enough, will transform our society. These are zones of eco-socialist transformation, a point of recaptured commons. These should consist of freely associated labor and anti-capitalist intention. We also need to have an eco-centric ethis: a conscious intention to heal the Earth.

Patrick Bond mentioned that one of the central aspects of debates about eco-socialism hinges on ideas of catastrophe (between David Harvey and Foster, and between Neil Smith and Joel Kovel). Joel replies that he thinks we ARE headed towards an environmental catastrophe, but that this is no different from the confrontation with mortality that all human beings have  confronted. What this requires is a transvaluation of our humanity, a deeper comprehension of what it’s been like to be human. It’s a clarion call to think much more deeply about our history and our relation to nature.

confronted. What this requires is a transvaluation of our humanity, a deeper comprehension of what it’s been like to be human. It’s a clarion call to think much more deeply about our history and our relation to nature.

To simply deny the gravity of our current crisis is just plain stupid, Kovel argues. Once you get engaged, things become very exciting. It’s the worst of times, but also the best of times. Who else has been able to rethink the entire structure of human civilization the way we need to do.

Roger asks a question about Kovel’s strategy. Not to throw classical Marxism at you, but what’s your relation to the state? In France there’s been a big debate with Badiou about how to proceed in relation to the state. Kovel replies that the state has a two-fold function: legitimation and accumulation. The latter always comes first. Social movements need to keep a cold eye on the state and make sure it doesn’t get away with anything. So this means to disengage?, Roger asks. Yes, that’s right, Joel replies.

Audience question about the SACP. Kovel talks about how the SACP is beholden to a long tradition of productivism: the idea that communism will just perfect the capitalist system. Kruzchev’s “we’ll bury you” statement as typical of this. But there are signs of a more progressive tradition in South Africa. Kovel says that he was very heartened by a recent statement of COSATU that is basically eco-socialist.

I asked a question about the turn towards fascism as a far more immediate result of climate chaos, in other words towards the securitization of the environment. Isn’t it likely that this is more likely outcome than autonomous eco-socialist collectives? Isn’t there a kind of teleology in your argument that autonomous eco-socialist groups will link up and form a new order? Kovel replies that history is still to be written and nothing can be assumed. We have a lot of work to do.

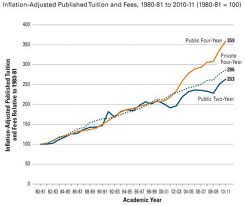

Next up, Michael Dorsey (Professor of Environmental Studies at Dartmouth College) presented on why these debates matter. The main point he makes is that climate change is WAY ahead of schedule. He shows lots of charts and graphs to illustrate this. Dorsey has been working with Artic Ice Institute near Darmouth, which has released a lot of information about ice thinning.

Dorsey then goes on to talk about vulnerability to climate change being concentrated in the global South, while those in the North are less vulnerable. Maplecroft Climate Change Risk Report shows that those who are getting most badly screwed by climate change are in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Andes, and the Himalayas.

Official solution is one of enclosures, either through cap and trade market approach or offset exchange approach. Both are characterized by market approaches. The capitalist is saved by doing this: Ken Newcombe (carbon marketer and World Bank Prototype Carbon Market): “carbon trading’s objective is to reduce the costs of emissions reductions for industrialized countries.”

Carbon markets are a failure: the EU Emissions Trading System has failed on a third attempt (Carbon Trade Watch, 2011).

But we also need to be worried about the devil: the money form. The Euro has fallen by by a third in recent years. UBS predicts a 70% collapse in EU CO2 prices on Nov. 19, 2011.

So, what next? What are our alternatives? California social movements rejecting market alternatives, and then WE ACT picks up this approach and takes it to a national plane. Now there’s a whole wave of legal movements growing in California. These legal strategies have been connecting up with global strategies, such as those articulated in the Cochabamba Declaration.

Climate Justice Now! Network Principles are based on eco-socialist principles.

Q: Do we continue to move from conference to conference?

A: It’s not that hard to jam events like COP. We should be kicking up much more of a ruckus. We should be using our energy to shut this shit down not to try to make carbon markets work more efficiently. I think this is a kind of Stockholm syndrome: people like the kidnapper. Those who are inside are there to whistle blow, not to have some kind of impact. What you have to remember is that it’s 1% at COP. There’s little difference between Wall Street and UNFCCC at this point. There is a revolving door between these characters: 1/3rd are totally in cahoots with capital, and another 1/3rd are close enough and willing to do consulting in order to make money. So 2/3rds are undermining progress, and there’s confusion in the ranks.

Roger: But we do have allies, even among traditionally tepid social actors. Example of International Trades Union Commission’s report on a Just Transition.

Michael: The poor DO care about the environment. They do more and expect more. We need to speak to them.